Authors / metadata

DOI 10.36205/trocar2.2022002

Abstract

Women suffering from endometriosis have always been misdiagnosed. Their misdiagnosis leads to years of suffering and pain before their illness is truly detected. Educating women about endometriosis is an important part in the management of endometriosis, however what appears to be more essential is raising awareness of the disease and its impact among primary health care professionals and the public. This lack of awareness is usually combined with a tendency to accept that pain is a part of menstruation. After years of conducting endometriosis education and applying endometriosis care to patients in our clinics in three different cities across Saudi Arabia – Jeddah, Makkah, and Riyadh – coupled with two pilot studies, we took the initiative of compiling this knowledge into this Endometriosis Coping and Awareness Bundle (ECAB) in an attempt to provide physicians and the public with a proper tool that supplements medical care. ECAB targets promoting endometriosis awareness in the medical, institutional, and social setting. It emphasizes the importance of putting endometriosis patients in the limelight and providing them with the support they need so they could feel victorious rather than victims. The message that this bundle is trying to relay is that our society has to overcome its cultural inertia and raise awareness of this misunderstood and neglected condition.

Introduction

The presence of endometrial-like tissues outside of the uterine cavity, otherwise known as endometriosis, is a chronic disease associated with pain in the pelvis, along-side infertility. Endometriosis is not a malignant disease, on the contrary, it is an estrogen-dependent, gynecological disorder. The side effects associated with endometriosis and the fact that it is a life-long inflammation, make it a critical disease that impacts the medical, social and economic aspects of a woman’s life (1). The causes of endometriosis appear to be multifactorial, involving genetic, immunological and environmental factors, with many theories postulating how it might have evolved (2). Women suffering from endometriosis often describe symptoms that simulate other conditions (3). The interplay of all these factors could cause a missed diagnosis or a diagnostic delay which could lead to some women getting a diagnosis up to 7 years later.

Endometriosis is a common gynecological condition around the world, reported in around 10% of women of reproductive age (4). Although endometriosis affects women during the prime years of their lives, it should be noted that there are also documented cases of women with endometriosis after menopause; it may also occur in adolescent girls (5). The most obvious complaint of women with endometriosis is pain. Additionally, endometriosis is in many women the cause of infertility and the deterioration of the quality of life with psychological impact (1). The situation relevant to endometriosis is no different in Saudi Arabia. A survey of the literature on endometriosis revealed only 10 studies conducted on Endometriosis in the Saudi population until the end of 2020. Two retrospective studies on gynecological laparoscopies performed by Sendy et al in 2017 and Rouzi et al in 2015, included 785 surgeries in total and reported a 13.5% prevalence of endometriosis (6, 7).

The treatment of endometriosis could either utilize medications or surgery or a combination of both. These two methods could prove effective, however not without side-effects. Furthermore, neither of these treatments wipes out the disease, as lesions that have been surgically removed can recur and discontinuing medications can cause symptoms to reappear (3).

Given that there are no known methods to prevent endometriosis at the current time, the best approach to assist the woman suffering from endometriosis is to effectively manage this disease through raising awareness and enlisting a team of multidisciplinary professionals, including but not restricted to a pain specialist, physiotherapists, gynecologists, and psychologists.

Educating women about endometriosis is an essential element of the process of managing endometriosis. A New Zeeland program on menstrual health and endometriosis education in secondary schools, which also observed age patterns of young women presenting for menstrual morbidity care, reported strong suggestive evidence for the first time that consistent delivery of a menstrual health program in secondary schools increases awareness of endometriosis and may promote timely presentation of young women to specialized healthcare services (8). What appears to be more critical however is raising awareness of the disease and its impact among primary health care professionals and the public. This lack of awareness is usually coupled with the normalization of pain during menstruation (9). A quantitative study conducted by Grundstrom et al in 2018 proved that women with endometriosis encounter difficulties with general practitioners when describing their symptoms. They further concluded that women all over the world seem to suffer diagnostic delay and normalization of their symptoms (9).

After years of conducting endometriosis education and applying endometriosis care to patients in our clinics, coupled with pilot studies (unpublished data) that we have conducted to better understand the perception of pain and prevalence of endometriosis, the concept of compiling this knowledge into this Endometriosis Coping and Awareness Bundle (ECAB) was conceived by the main author and supported by the coauthors and their team over the past one year in an attempt to provide the public with a proper tool to implement purposely designed activities that raise awareness about endometriosis among health care providers, women, men, adolescents, teachers and wider communities.

Material Method

We developed the Endometriosis Coping & Awareness Bundle (ECAB) with women who suffer from endometriosis in mind. The bundle was formulated after our Group of experts conducted extensive investigation into endometriosis that included pilot studies, field work, and awareness campaigns in three different cities across Saudi Arabia: in Jeddah, Makkah, and Riyadh.

After the establishment of the Saudi Endometriosis Group in 2013, the first of its kind in the Middle East, this Group has lead several activities to raise awareness and educate on endometriosis including medical conferences and annual meetings, developing a website dedicated to the disease, producing brochures in Arabic and English, interviews and appearances on television, public awareness campaigns in malls, universities and schools, social media campaigns and several events to highlight the impact of endometriosis on women’s health most prominent of which was the ‘Art of Endometriosis’ event that featured photographers and painters.

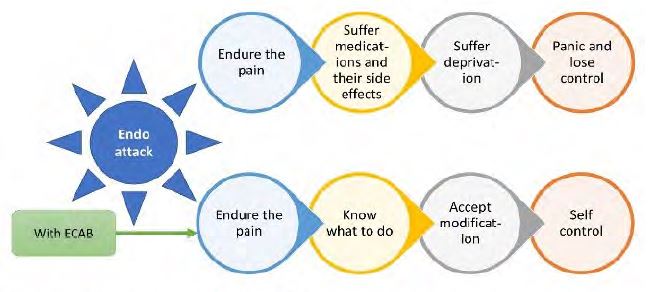

The ECAB was a labor of tailored duty work during and outside the daily clinical working hours. It was designed after our Group observed a rising need to help endometriosis patients to cope with the painful attacks and to lead a productive and optimistic lifestyle. This bundle is a compilation of procedures, techniques, packages, and plans to help improve the management outcome of endometriosis. It was developed in an attempt to turn around the miserable quality of life that women with endometriosis have to strive through taking into consideration the physiological, psychological, and social impact of this disease. Instead of enduring pain, deprivation, medications and their side-effects during an endometriosis attack, women who have been targeted by this awareness bundle would instead endure their pain while knowing how to handle their endometriosis attack, accepting lifestyle modifications, and practicing self-control (Figure 1).

Its implementation requires teamwork headed by the primary endometriosis laparoscopist and the endometriosis educator. More physicians, surgeons, nurses, technicians, and volunteers can be enrolled if willing.

Pilot studies

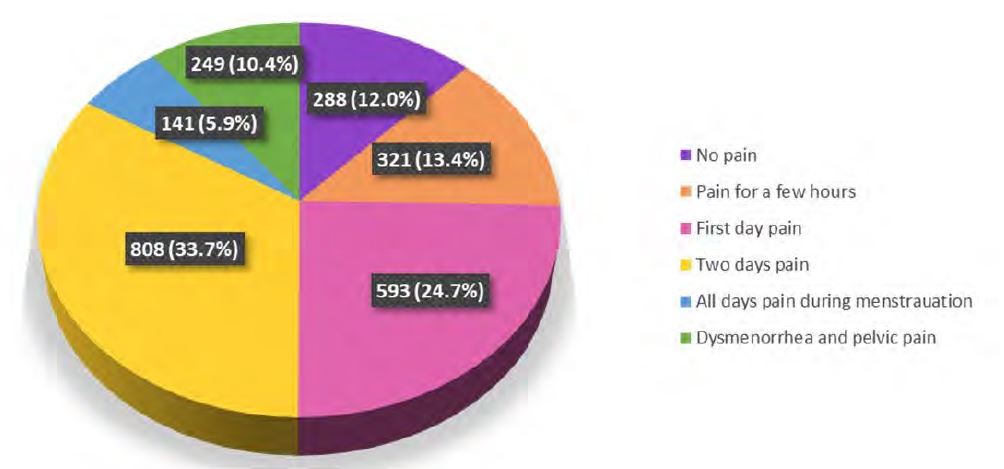

Two pilot studies were conducted by our team a few years ago (unpublished data), the results of which were considered the basis of developing ECAB. The studies were approved by a local ethical committee and all participants were consented. The first study assessed the incidence of dysmenorrhea among Saudi girls. The study included healthy unmarried girls attending school or enrolled in their first years of college. A total of 2400 Saudi girls under the age of 21 years filled a questionnaire that was circulated via email to 5000 participants. Our data revealed that the prevalence of dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain among Saudi girls was 88%. More than 1400 (58.3%) of these girls had dysmenorrhea during the first 2 days of menstruation, while only 141 (6%) of them had it throughout menstruation. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea along with pelvic pain outside the menstrual phase was reported in 249 (10.4%) of the surveyed girls, whereas only 288 (12%) reported no pain or dysmenorrhea at all (Figure 2).

The study also surveyed the girls to check whether any of them sought medical advice for their dysmenorrhea. Around 300 (14%) of those surveyed went to see a doctor, and of those 55% had a transabdominal pelvic ultrasound, 4% of which showed an ovarian cyst. None of the girls checked by a doctor were prognosed with endometriosis. While these girls could have been the victims of endometriosis, no attempt at raising awareness or discussing the possibility that they could have an endometriotic lesion was mentioned.

The second pilot study was conducted during awareness campaigns that were held at malls, universities, or schools. During each campaign, short questionnaires were distributed to understand which medium was of preference for women who wanted to learn more about endometriosis. Of the 500 women surveyed, around 304 (60.8%) women mentioned that they would prefer social media as a way of disseminating messages relevant to endometriosis. The remaining 113 (22.6%) opted for television campaigns and programs, 57 (11.4%) women preferred the internet, 20 (4%) chose the physician’s clinic, and 6 (1.2%) women selected other channels.

Results

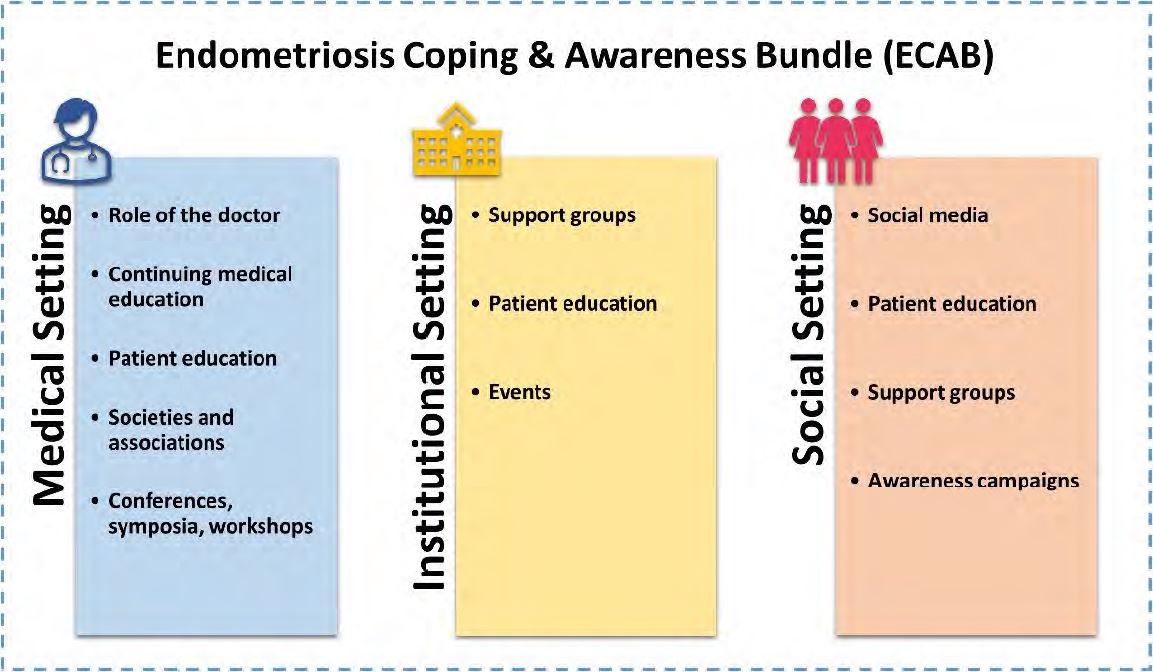

The results of our above pilot studies coupled with our knowledge of endometriosis care, collaborative efforts and raising awareness along the years has led us to develop the following elements of the ECAB in the medical, institutional, and social setting (Figure 3).

Medical setting

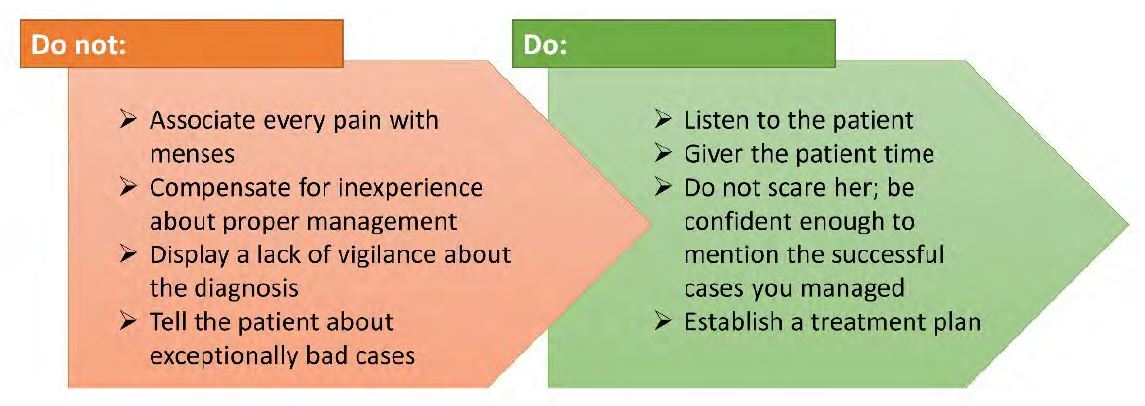

The medical setting involves developing educational programs for both the patient and the medical practitioner. At a primary level, the medical practitioner should be educated with the proper methods of communicating with a patient, particularly with someone suffering from endometriosis. In general, and throughout our practice, we have noted that medical practitioners tend to startle women when for example they try to compensate for their inexperience of proper endometriosis management, display a lack of vigilance, and mention exceptionally bad cases of endometriosis (10). As a result, the women suffering from this disease become more anxious and depressed. Instead, it is advisable to mention the many successful cases of endometriosis that have been managed. A proper management plan would include listening to the patient, giving her time to understand and ask questions, and eventually calm her down and establish a treatment plan, even if it involves referral to a proper center (Figure 4).

Medical practitioners should also continue to expand their medical knowledge and learn about the advances in endometriosis care. This can be achieved by attending continuing medical education sessions, conferences, symposia, and workshops. It is advisable that the medical practitioner join a society or association with endometriosis as its primary target. It is of interest to mention that 10 years ago there was hardly any medical conference devoted to endometriosis alone. Endometriosis used to be discussed among other subjects in general gynecological meetings. Nowadays there are about twenty endometriosis medical conferences per year around the globe.

Patient education is another important element that physicians should practice at their clinic. Not only that, but patient education spans the three settings detailed in our ECAB. Teaching women about endometriosis is of utmost importance, and special attention should be paid to girls in their teenage years, as this category is mostly left out when developing brochures or conducting awareness. Utilizing patient education materials such as written guides, videos, audiotapes, books, and pamphlets can greatly increase a patient’s awareness of her chronic disease but does not replace an on-going discussion with her health care provider. The healthcare provider should inform patients about ways to deal with their chronic pain so that they can attend school, participate in sports, or enjoy social events. Compliance and medical follow-up will improve significantly for patients with dysmenorrhea or endometriosis who are active participants in their health care.

Creating educational material for endometriosis begins by obtaining feedback from patients with endometriosis through venues such as focus groups, questionnaires, and peer review of written material. Then the educational material can be developed in a personal, conversational style with a questionand- answer format. It is important to know that patients want to have their feelings acknowledged without a condescending tone. They appreciate nonjudgmental statements and want information to be clear and simple with limited medical jargon and abbreviations. Providing a list of additional resources such as web sites and books is of added value for these patients (11).

Institutional setting

In the institutional setting, psycho-educational interventions designed to facilitate adaptation to the challenges of chronic disease and promote self-management were introduced in the United Kingdom in 2002 (12). Participants were found less anxious, less depressed, and scored better on all of the self-management techniques after self-management training; they felt more in control of their disease.

Patient education classes and group counselling in the institutional setting are pivotal for any endometriosis awareness program and well known to decrease anxiety and depression in endometriosis patients and improve their quality of life. A randomized controlled trial was conducted by Farshi et al in 2020 on 76 women with endometriosis randomized to either intervention – a seven-week self-care group counselling sessions- or control which involved routine care. The study revealed a significantly lower score of trait anxiety and state anxiety in the intervention group. Moreover, the mean score of quality of life for physical health and for mental health were significantly higher in the counselling group than in the control group (13).

The benefits of a support group are many. They let the woman know that she is not alone, allow her to learn new coping techniques and share her experience. In general, the patient support group for endometriosis should include a group of patients sharing the same medical condition, endometriosis in this case, offer a forum for comfort and encouragement, be non-profitable, provide free printed or digital information or suggest social media accounts. The purpose of this support group would be to create networking with other patients in-person or even virtually. An important point to highlight about support groups is that the person leading this group should emphasize listening, know the facts, be assertive, and understand how to lighten the mood and make the experience a fun one. Therefore, it is advisable that the session leader be a health professional such as a nurse or a non-health professional but with extensive knowledge of endometriosis and firsthand experience in this condition.

The role of the medical practitioner should be extended to the support group. It is essential that the practitioner try to attend some of these sessions in show of support and also to answer any ques t ions that might a r ise. It is also important that the medical practitioner who participates in patient education or support groups be a gynecologist with knowledge of laparoscopic surgery, knowledge of female sex hormones and someone who regularly attends continuing education sessions relevant to endometriosis.

Social setting

Using the internet for information and support has become one of the main outlets whereby patients search for information. In 2013, online health Information was accessed by 43% of adults in the United Kingdom and 72% in the United States (14). The purpose of going online was to read about other people’s experience of a health-related problem in 25% of those accessing the internet or to find others with the same problem in 16% of those accessing it. Shoebotham et al in 2016 explored the therapeutic affordances of an online support group among 69 women with endometriosis. The analysis of the women’s perception revealed an array of positive aspects that benefited women when it comes to using an online support group. The four therapeutic gains listed by the authors were connection, exploration, narration and selfpresentation (15). Similar findings were reported by Merolli et al in 2014 for people with chronic pain (16).

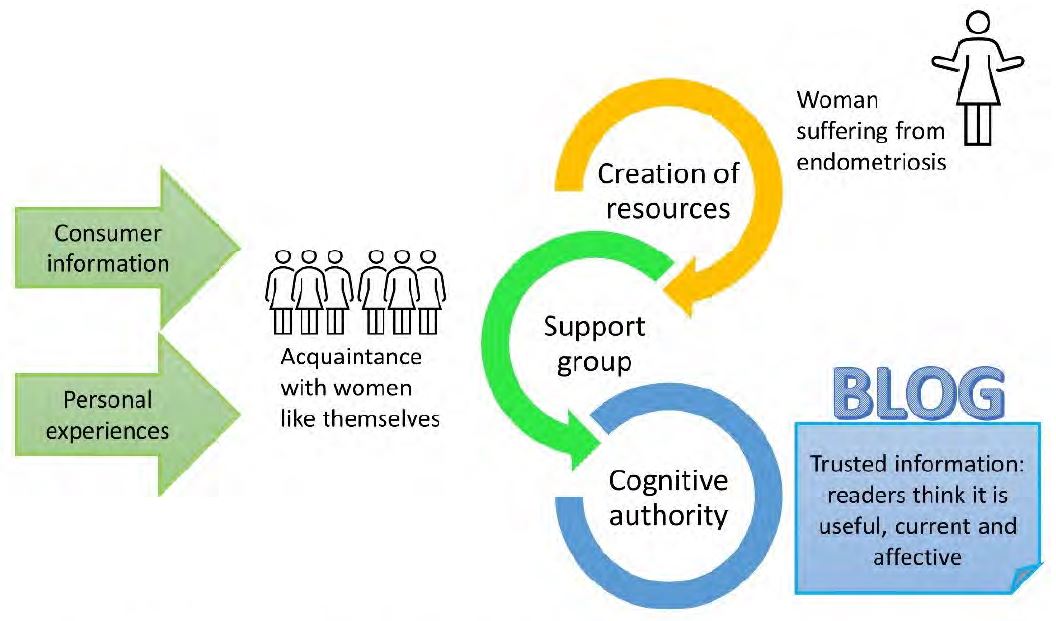

Women suffering from endometriosis could also benefit from information available on the internet, particularly on blogs. Research conducted by Neal and McKenzie in 2011 revealed that blogs that were authored by women with endometriosis who shared their experiences had informational value to other women, particularly when it comes to providing them with emotional support and increasing their knowledge. Furthermore, the endometriosis patient who blogs about her experiences was reported to determine authority of information sources through both cognitive and emotional methods (17).

To develop an endometriosis blog, it is important for the blogger to have a shared experience with her audience, a fellow sufferer from endometriosis. The blogger normally starts by searching for information and formulate her resources. Following this step, the blogger should acquaint herself with others suffering from endometriosis and this would ideally happen through participating in support groups. This will not only allow the blogger to collect ‘consumer information’, but also share personal experiences. The blogger would then proceed to share her experiences online through a blog or discussion forums. The shared information would gain the trust of the readers who think of it as useful, current, and affective. Thus, the blogger would eventually become a cognitive authority and this information resource would become a useful blog (Figure 5). It is worth noting that the blogger should maintain an explicit privacy policy to conceal personal profiles of the patients.

Social media has also become a major player in the impact on wellbeing (18). Apart from accessing or sharing knowledge, social media has the power of sharing emotions that can be of great support to endometriosis patients if properly used. A recent study by Wilson et al in 2020 found that Malaysian women with endometriosis used social media to share information about the disease, support each other emotionally, and build friendships (19). Out of all social media platforms, Facebook is considered the most popular, and when posts were written by professionals, they were usually very informative, evidence-based, and frequently visited. One study, looking at Facebook pages related to endometriosis emotional support and education, has concluded that clinicians or healthcare workers should inform their patients of available support groups on social media as part of their treatment (20).

Discussion

Traditionally, the doctor-patient relationship has always been limited by the doctors’ availability, busy schedule and free time outside the operating room and clinic hours. Hence, patients with chronic disease, like endometriosis, who are likely to have recurrent painful attacks at different times and in different styles, may feel at the losing end in this relationship as they lack proper attention and awareness to their condition and prompt coping techniques to live comfortably despite the medical and surgical treatments they were offered.

ECAB was designed to bring these women into the limelight and make them the center of attention of the physician. It involves gynecologists’ participation in addition to official patient education classes with patient group support along with social media involvement and active patient participation. As a result, the patient will be satisfied, informed, and coping well with the painful endometriosis attacks. Interestingly, this achievement does not stop here; placing women in the driver’s seat and in control of their symptoms, will prompt these women to help others and share their knowledge through support groups or blogging. The wheel of ECAB will therefore keep running indefinitely. Moreover, it is plausible to think that this proliferation of women in control of endometriosis will cross borders and spread all over the globe as long as the internet is functioning, and language is instantly translated.

A group of Saudi women with endometriosis have hooked themselves to a Chinese endometriosis support group and are currently exploring the tricks and coping techniques in a different dimension hoping that they could improve their lifestyle and combat the disease. We are hoping that with ECAB, a similar intermingle arises between communities around the world, whether African, American, European, or Asian or other population, and will help fight the disease and eliminate its suffering. Our first pilot study has revealed a lack of support and care when treating adolescents with dysmenorrhea. This will ultimately lead to a number of misdiagnosed cases of endometriosis.

A cross-sectional study conducted by Hashim et al revealed an 80% prevalence of dysmenorrhea among female medical students in Saudi Arabia (21). This number is quite close to our results, and their conclusions are in line with ours: awareness campaigns should be frequently implemented to improve the quality of life of patients with dysmenorrhea and possible endometriosis (21).

Furthermore, implementing awareness programs has been shown to decrease the diagnostic delay associated with endometriosis (22). These delays impact women and healthcare providers alike. Women who are misdiagnosed lead a low quality of life and suffer physically, psychologically, and financially. The same applies to healthcare providers who could ultimately save time and resources if they diagnosed in a timely manner.

Support groups are elemental for women with endometriosis as they provide emotional support and act as a resource of sorts. It is worthy to mention that self-care and being part of a support group is not tender loving care. This is a system that can take the management of endometriosis to a different level away from medical or surgical interventions. Social sharing of emotions is a well-studied phenomenon since its introduction by the famous social psychologist Bernard Rimé in 1991(23), who also proved later those positive emotional experiences fuel subjects’ thinking (24). In fact, Rimé’s continued research led him to say that “sharing positive emotions not only boosts individual’s positive effect, but it also enhances their social bond” (24).

On the other hand, the issue with sharing information and emotions through blogs or on social media is that the lack of accuracy and the inadequate quality of the information could leads to an infodemic (25). The impact of the internet – social media in particular – on the wellbeing of an individual still needs guidance and monitoring, some discern that the method by which people utilize social media for their wellbeing is what could ultimately affect the outcome on their health, whether positive or negative (18). Empowering women with endometriosis is of utmost importance. These women will no longer feel like a victim but rather victorious, as they feel more in control of their disease and turning endometriosis from a painful condition with no hope of coping to one where she is confident and in charge.

There is a lack of understanding between healthcare professionals about endometriosis, and we would therefore highly recommend that healthcare professionals, and physicians in particular receive adequate training on possible signs and symptoms of endometriosis. Additionally, endometriosis medical care should include guidance on how to help those patients socially, sexually, and psychologically. It is true that more research on the pathogenesis, prognosis and diagnosis is much needed to help diagnose endometriosis, the key remains however in increasing the public’s awareness of the disease. ECAB was constructed, through its three settings, to provide women with endometriosis with the knowledge and the confidence to cope with painful attacks skillfully.

Conclusion

They may even save themselves from unnecessary medical or surgical interventions; not to mention the positive impact on health care expenses and reducing the burden on doctors. The message that this bundle is trying to relay is that our society has to overcome its cultural inertia and raise awareness of this misunderstood and neglected condition.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Ms. Rola El Rassi for allowing this bundle to be brought to life, without her it would have been impossible to compile this work.

References

Fig. Endometriosis and quality of life

Fig.2 Prevalence of pain and its duration during menstruation in Saoudi girls. Data is presented as numbers (percentage, %)

Fig.3 Methods for approaching and education patients with endometriosis

Fig.4 The direct role of the doctor

Fig.5 Developing an endometriosis blog