Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar5.2024021

Abstract

Background: The role of Hysteroscopy in common gynecological disorder is important. Adenomyosis is due the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. Hysteroscopy is not the first line treatment for Adenomyosis but it allows direct visualization of the uterine cavity. It helps in obtaining biopsy samples followed by further management.

Materials and methods: The literature was searched till June 2024 for the non-systematic review related to the role of Hysteroscopy in diagnosis and management of Adenomyosis. It was obtained from databases such as PubMed, Embase, google scholar, web of science, Science direct and Cochrane study.

Outcome: Due to the developed imaging techniques, it has become easier to identify Adenomyosis pre operatively. The underlying mechanisms of adenomyosis remain largely unclear, even though the condition is quite prevalent, there is potential for pre-histologic identification, and the symptoms can significantly affect women’s health. The advantage of visualizing the uterine cavity directly is achieved through hysteroscopy. Resection may be carried out utilizing mechanical instruments and/or bipolar electrodes; however, this procedure is only suitable in instances where adenomyosis is observable via hysteroscopy. Intraoperative ultrasound in Hysteroscopy can help confirm the diagnosis of adenomyosis, these sings include a spherical uterus, marbled uterine surface or any cyst on the uterine wall. It is crucial to select appropriate patients for this office-based procedure, as it generally demands more time and may lead to increased discomfort.

Conclusion: Due to Hysteroscopy the management of Adenomyosis has been revolutionized. It allows biopsy from the particular area which increases the diagnosis of this problem. Finally operative Hysteroscopy can be done in superficial Adenomyotic nodules and for diffuse superficial Adenomyosis

Introduction

The term “adenomyosis” refers to the endometrial tissue (stroma and glands) existing within the myometrium; heterotopic endometrial tissue foci are linked to varying degrees of hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells (1). However, the definition of the disease still has no consensual definition yet. It can be as simple as disrupting the endometrialmyometrial junction to more than 8 mm depth, or it can even link the required invasion depth to the thickness of the myometrium (2). It can manifest as either localized or diffused, depending on the extent of myometrial invasion. Diffuse adenomyosis is characterized by a large intermingling of endometrial stroma and/or glands and myometrial muscle fibers, resulting in an enhanced uterine volume that is correlated proportionally with the lesion’s extent. The focal adenomyosis is typically located in the myometrium as an aggregate of a single node, with a spectrum of histological characteristics that can range from mostly cystic (“adenomyotic cyst”) to mostly solid (“adenomyoma”) (3,4). Because adenomyosis could only be identified with certainty on histological specimens obtained following hysterectomy, the estimated incidence of the condition ranged between 5% and 70% in retrospective investigations (5). Pregnancy and prior uterine surgery appear to be risk factors for this condition, which is typically diagnosed in women of reproductive age.

Though the precise mechanisms underlying the development of adenomyosis remain unclear, current understanding holds that the deep endometrium, which invaginates between the bundles of smooth muscle fibers in the myometrium, is the source of adenomyosis or adenomyoma, primarily following uterine traumatic events (6,7). Therefore, it seems that uterine manipulations are a significant risk factor for invasion of endometrial cells in the myometrium (8). Given their shared embryological origin from the Müllerian ducts of the endometrium and the subjacent myometrium, endometrial tissue contains metaplastic myometrial cells leading to direct proliferation, which is believed to be a potential pathogenetic mechanism for uterine adenomyotic cysts. The endometrial tissue lining in these cystic structures is associated with myometrial tissue containing hemorrhagic material (7, 9).

Adenomyosis was recognized as a significant condition of the female reproductive system, and the use of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did start a significant shift in this understanding. By using these techniques consistently, it is possible to visualize the aberrations of the myometrial architecture without an invasive procedure and to differentiate between the pathologies of the junctional zone and the outer myometrium. The junction zone differs from the outer myometrium both physically and functionally, and it is dependent on hormones, unlike the latter (7). The primary cause of uterine auto-traumatization has been observed to be deregulated in these contractions in adenomyosis and endometriosis patients, which results in hyperperistalsis and dysperistalsis (8). The pathophysiology of adenomyosis is poorly known, despite the great incidence of the condition, the potential for pre-histologic detection, and the severity of the symptoms that negatively impact women’s health (10). The lack of proper classification is a result of this ignorance. Similar to endometriosis, adenomyosis can take many different forms, from straightforward thickening of the junction zone to localized, cystic, or widespread lesions. The well-defined focal lesions might manifest as either a muscular or a cystic lesion. Diffuse lesions have poorly defined borders that can affect both anterior and posterior uterine wall totally, increasing the volume of the uterus and producing an uneven appearance.

Symptoms

It is challenging to associate adenomyosis to a single pathogenic symptom. Adenomyosis symptoms include pelvic pain (including dysmenorrhea, persistent pelvic pain, and dyspareunia), decreased reproductive potential, abnormal uterine bleeding, and oedema; however, about 30% of individuals have no symptoms at all (11). Moreover, concurrent morbidities, of which endometriosis and fibroids are the most common, may conceal the causal relationship between the disease and the symptoms by having comparable symptomatology. It’s unclear how common adenomyosis is as a stand- alone pathology; estimates range from 38% to 64% (12).

While there is disagreement over the precise correlation between adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea, reports of the condition’s incidence range from 50% to 93.4% (13, 14, 15). Compared to women with just fibroids, an odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI 1.8-6.4) was observed in women with adenomyosis and leiomyomas for having greater dysmenorrhea (14, 16). There was reported to be a linear relationship between the degree of dysmenorrhea and the level of adenomyosis (17). Although the exact cause of dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain in women with adenomyosis is unknown, prostaglandins may be a significant factor. In uterine adenomyosis, the existence of nerve fibers is still up for debate, although in severe endometriosis, their presence has been cited as a potential reason for discomfort (18, 19, 20).

The causal relationship between adenomyosis and co-existing morbidity, such as uterine fibroids and the inclusion of multiparous women, is difficult to establish. Nonetheless, it was reported that nulliparous women, who were diagnosed with diffuse adenomyosis, had an ultrasound examination indicating a higher frequency of irregular uterine bleeding (16). For every extra adenomyosis characteristic, there was a substantial 22% increase in menstruation [OR 1.21 (95% CI: 1.04–1.40) (12). An attempt was made to quantify the blood loss by classifying the clot size into four groups (21). A statistically significant association was observed between the degree of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and the depth of adenomyosis (21).

The uterine myometrium consists of two distinct components: the outer myometrium and the inner myometrium, which is also referred to as the sub endometrial layer or junctional zone. The inner myometrium shares similarities with the endometrium and experiences cyclical changes, originating from Müllerian tissue. In contrast, the outer myometrium is derived from non-Müllerian, mesenchymal tissue (22). Patients with adenomyosis and endometriosis experience dysperistalsis of cycle- dependent contractions of the junctional zone, which disrupts uterine tubal sperm transport and causes a more noticeable retrograde menstrual cycle (23). Evidence of effect of adenomyosis on fertility is increasing, especially in the face of disruption of the myometrial structure and altered endometrial function (24).

Materials and Methods

A range of articles was evaluated for the nonsystematic review concerning diagnosis and management of adenomyosis, focusing on the role of hysteroscopy. The literature was gathered through a comprehensive search of multiple databases such as PubMed, google scholar, Embase, Web science, Science direct and the Cochrane database. The selection process involved filtering articles based on the availability of the full texts, publication year and topic relevance up to June 2024. Studies detailing diagnosis and management of adenomyosis and its connection to hysteroscopic treatment were included in the review. The search utilized keywords such as Adenomyosis, Hysteroscopy, and role of Hysteroscopy in Adenomyosis.

Discussion Hysteroscopy

The benefit of direct uterine cavity vision is provided via hysteroscopy. It has been demonstrated that the technique can be performed in an outpatient setting with good tolerance by employing contemporary small barrel rigid hysteroscopes, the atraumatic vaginoscopy method, and a watery distention medium (25). Furthermore, in US patients, a study showed 27% of anomalies and no access failure or consequences. The interobserver difference, even across professionals, is a current limitation of hysteroscopy, making proper multicentered investigations to validate the significance of the disparate findings practically impossible (26). Hysteroscopic examination of the surface of endometrium can identify minor lesions that may be indicative of adenomyotic alterations in the myometrium, though their pathological significance has not yet been established.

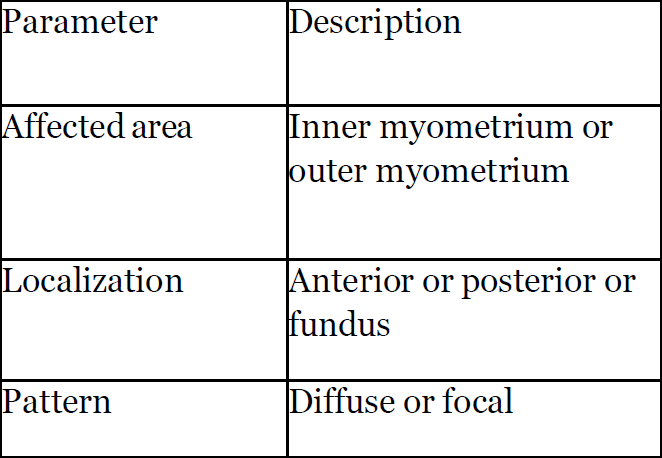

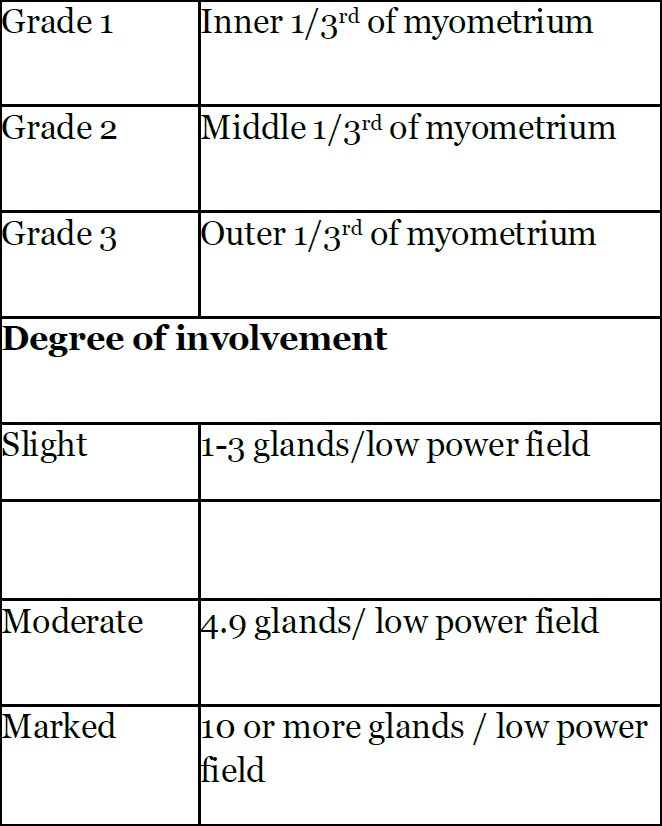

The international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) included important parameters in classification such as area affected, localization of adenomyotic changes, its pattern and type and volume (Table 1).

Endometrial alterations such as increased vascularity, a strawberry-like appearance, defects within the endometrium, and the presence of submucosal haemorrhagic cysts are indicative of adenomyosis (27, 28). Transvaginal sonography revealed a cystic transparent region in the fundal area that looked like a protruding structure inside the uterus. Histology results from a biopsy of the cyst’s bed revealed adenomyosis (28). As the significance of the inner myometrium

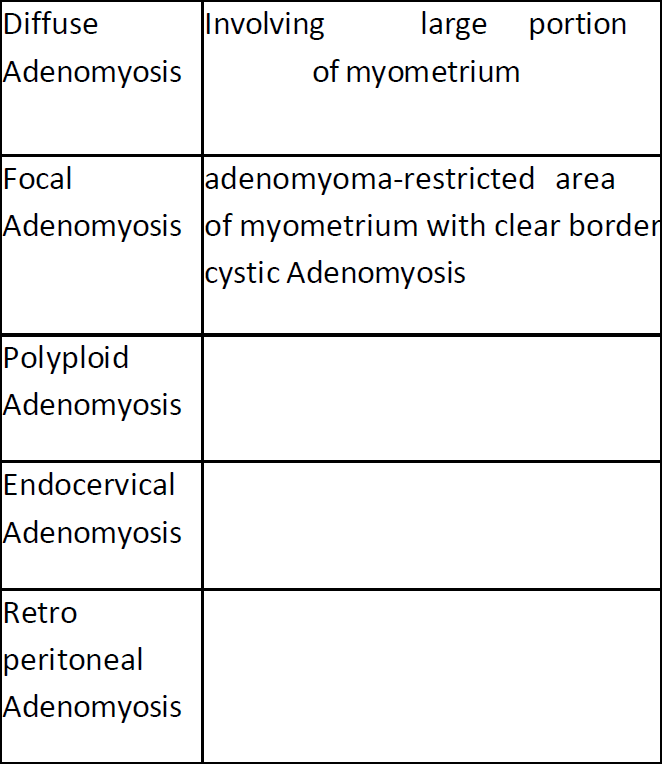

becomes more apparent, patients experiencing abnormal uterine haemorrhage, pain, or infertility should not only have their uterus explored; instead, their inner and outer structure of myometrium should be examined. The hysteroscopic examination reveals pathognomonic indications of adenomyosis, including endometrial implants on the pseudo-cystic wall and neovascularization, along with cysts filled with chocolate dye. It becomes necessary to combine hysteroscopy and ultrasound. Clinical classification of adenomyosis suggested the area involved in adenomyotic changes (Table 2).

By using a hysteroscopic technique, myometrial and endometrial samples can be taken with ultrasound or visual assistance. The spirotome can be inserted into the uterus cavity using the Trophy hysteroscope’s diagnostic sheet as a guide. The corkscrew is precisely positioned in the direction of the sonographically suspicious location under ultrasound guidance. Following agreement on a position, the cutting tool is advanced and a one-centimetre cut biopsy is obtained. The results of an endo-myometrial biopsy revealed a poor sensitivity of 54.32% and a large percentage of false negatives in cases of profound adenomyosis.

The specificity of the biopsy was found to be 78.46% (29). Conversely, it has been found that the sensitivity of ultrasonography is 72% (30). It is possible to conduct a direct forwarded biopsy using the Spirotome (Bioncise) and get a representative tissue sample for additional analysis, because the diagnosis of adenomyosis appears to depend on the continuity of endometrial tissue infiltration into the myometrium, using the Spirotome to perform a biopsy provides the opportunity for additional research to identify potential differences between adenomyosis seen by imaging in patients of reproductive age and specimen in hysterectomy. It has been shown that by using spirotome under USG guidance, Adenomyotic cystic areas can also be addressed even in cases where intracavitary components are not visible (9). This device makes a channel and provides hysteroscopic access to the structure allowing further treatment with bipolar coagulation or resection to follow. The availability of direct access and the option for endomyometrial biopsies now allows for the correlation of ultrasound images with histological findings, eliminating the need for hysterectomy as required in earlier studies (31). The hysteroscopic method for addressing adenomyotic lesions offers the benefit of preserving the outer myometrium (9). Unlike the hysteroscopic resection of uterine fibroids, which typically demonstrates complete healing of the uterine cavity during postoperative control hysteroscopy, followup examinations after adenomyomectomy or the dissection of an adenomyotic cyst consistently reveal a defect in the uterus (31).

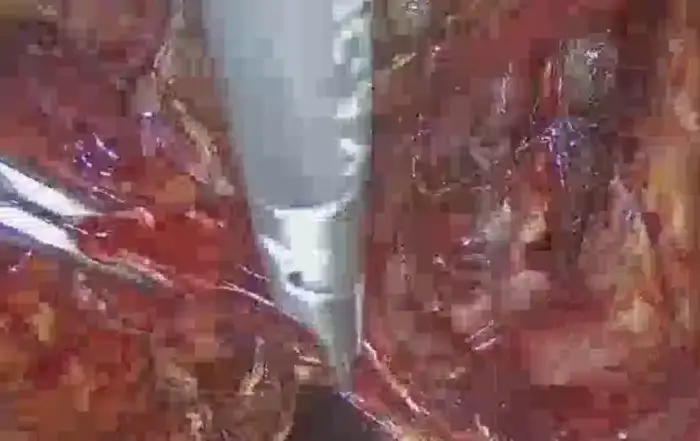

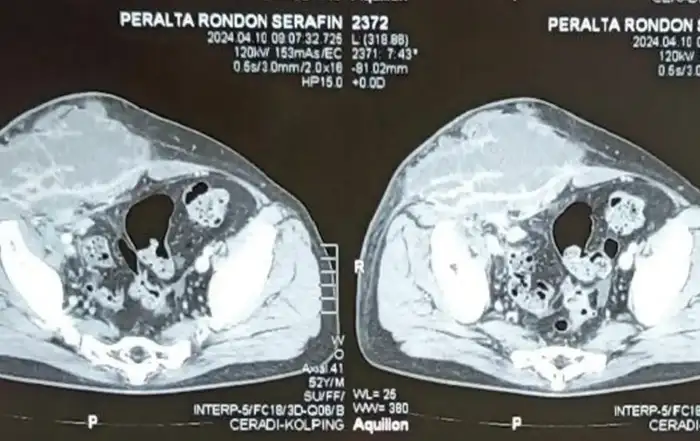

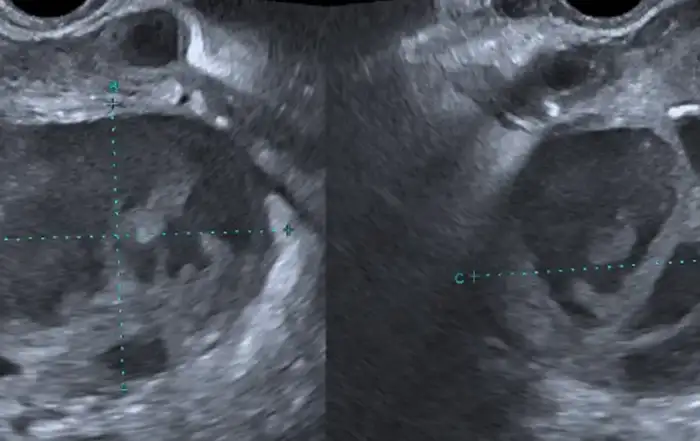

The reason for this remains uncertain, but it may be related to the infiltrative nature of the condition, which leads to inadequate healing in the sub-endometrial area. The group of patients in which there is focal or localised adenomyotic, the benefits of hysteroscopic resection is superior to the risks involved than in diffuse adenomyotic changes (Figure 1), this also includes the reproductive functions. Molitor’s criteria was suggested for Grading of adenomyosis (24). This grading suggested the degree of involvement of adenomyotic changes (Table 3).

Office Hysteroscopy

Enucleation has been recommended as a treatment option for focal adenomyosis measuring less than 1.5 cm in diameter and located near the endometrial cavity (32). This procedure can be performed using mechanical instruments and/or bipolar electrodes, but it is only applicable in cases where adenomyosis is visible through hysteroscopy. The underlying principle is that adenomyosis can be removed with minimally invasive dissection, which can be conducted in an office environment utilizing mini-hysteroscopy and a resectoscope. The technique employed in outpatient settings mirrors that used for submucosal myomas with intramural components. Resectoscope excision can be achieved in an office setting with the use of a mini resectoscope; however, the available evidence regarding the effectiveness of this surgical approach for treating adenomyosis is limited (33). In this context, it is important to identify patients who are suitable candidates for this procedure in an office setting, as it typically requires more time and may cause additional discomfort.

Conclusion

Due to the imaging techniques, it has become easier to identify adenomyosis pre operatively. The junction zone is distinct from the outer myometrium in both its physical characteristics and functional roles and its properties are influenced by hormonal activity. The underlying mechanisms of adenomyosis remain largely unclear even though the condition is quite prevalent, there is potential for pre-histologic identification and the symptoms can significantly affect women’s health. The absence of a comprehensive classification stems from this lack of awareness. Like endometriosis, adenomyosis can manifest in various ways ranging from simple thickening of the junction zone to localized, cystic or extensive lesions. Adenomyosis cannot be easily linked to a singular pathogenic symptom. The condition presents a range of symptoms such as pelvic pain (which encompasses dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain and dyspareunia) reduced reproductive capacity, irregular uterine bleeding and swelling. Concurrent morbidities particularly endometriosis and fibroids can obscure the causal link between the disease and its symptoms due to their similar symptoms’ profiles.

The advantage of visualizing the uterine cavity directly is achieved through hysteroscopy. Research has shown that this procedure can be successfully conducted in an outpatient environment with patients exhibiting good tolerance by utilizing modern small barrel rigid hysteroscopes, the atraumatic vaginoscopy technique and a fluid distension medium. The variability in observation among different professionals remains a significant limitation of hysteroscopy rendering it nearly impossible to conduct effective multicentred studies to confirm the importance of the varying results. While hysteroscopic evaluation of the endometrial surface can detect subtle lesions that might suggest adenomyotic changes in the myometrium, the pathological relevance of these findings has yet to be determined. Hysterectomy has traditionally been the most common approach for managing this chronic condition. There have been notable advancements in the diagnosis of adenomyosis prior to surgical intervention particularly in understanding the importance of tailored treatment strategies that take into account the patient’s age, aspirations for future pregnancies and specific symptoms. Operative hysteroscopy may serve as a suitable therapeutic approach for superficial adenomyotic nodules and diffuse superficial adenomyosis (34). However clinical failure is high and this procedure reduces the chance of hysterectomy by only 30% (35). The accuracy of hysteroscopy in adenomyosis had sensitivity of 40.74% and specificity of 44.62% and adding endomyometrial biopsy to TVS improved specificity of 89.23% (36). As depicted in the below images, the adenomyotic changes are seen on all four walls (A) and adenomyotic changes seen over fundus (B).

References

Table1: The international federation of gynecology and obstetrics group included important parameters in classification.

Table2: Clinical classification of adenomyosis

Figure 1: Adenomyotic changes seen on all four walls (A). Adenomyotic changes seen over fundus.

Table 3: Grading of adenomyosis (Molitor’s criteria) (24).