Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar5.2024013

Abstract

Hysterectomy is one of the most performed procedures for gynecological conditions worldwide. Due to the increased rate of Cesarean section, many patients undergoing subsequent surgeries like hysterectomy have a history of this procedure. Cesarean section usually induces the adherence of the bladder onto the uterus and dissecting it away becomes more difficult and exposes to injuries. In this paper, the authors report a case of a ventrofixed uterus, discuss risk factors, and underline some tips and tricks to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy in such patients.

Patients with repeated pelvic surgeries including multiple Cesarean sections, infectious complication after pelvic surgery, low pelvic pain after prior Cesarean section and infertility should be cautiously considered as being at particular risk for ventrofixed uterus. Clinical examination can help in determining the position and the mobility of the uterus considering the anterior abdominal wall. Imaging in very informative using ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). During surgery, anatomy guides the surgeon, and the preoperative information will help in preventing injury mainly to the bladder. The operating time is long but can be shortened when the surgeon plans the surgery in accordance with the preoperative information. Surgeons should be aware of the risk of ventrofixed uterus and how to conduct the workup and surgery for hysterectomy in such patients using some tips and tricks developed in this paper. This could help better counsel the patient and reduce the complication rate which is associated.

Introduction

Hysterectomy is one of the most performed procedures for gynecological conditions worldwide (1,2). When the vaginal route is not possible, the laparoscopic approach is preferred to the abdominal one for benign diseases (3). Due to the increased rate of Cesarean section (CS), many patients undergoing subsequent surgeries like hysterectomy have history of this procedure (4). This exposes to pelvic adhesions which can complicate the surgery in terms of prolonging the operating time and increasing the risk of intraoperative organs’ injuries.

CS usually induces the adherence of the bladder on the uterus and dissecting it away becomes more difficult and exposes to injury. In fact, the most challenging part during hysterectomy in patients with previous CS is the bladder dissection due to these adhesions. It has been reported there to be a higher risk of urinary complications in patient with history of CS compared to those without this history (5). When the whole of the anterior wall of the uterus has dense adhesions to the anterior abdominal wall, the scenario is even more complicated and if no attention is paid to some tips and tricks, the uncertainty during surgery, prolonging the surgical time, and the risk of injury to the bladder is even the highest. Adherend uterus to the anterior abdominal wall (ventrofixed uterus) has been reported in 14,9 to 17,9 % of hysterectomies for benign indications associated with previous CS (4,6). When a surgeon is mindful of the risk surrounding a surgical procedure, he is prone to recognize any complication. Thus, even a difficult surgical condition can be well anticipated, and the surgeon can better counsel the patient and arrange for preoperative and, if required, intraoperative urological assistance (7).

In this paper, the authors report a case of ventrofixed uterus, discuss risk factors, and underline some tips and tricks to performing laparoscopic hysterectomy in such patients.

Case

A 41-year-old, para three, gravida three has been referred for better management of uterine fibroids complicated with heavy menstrual bleeding. She had three CS with transversal parietal incisions, the last one, three years ago, was associated with tubal ligation. There were no details about reperitonization of the lower segment or the presence of adhesions at repetitive previous CS.

She complained of heavy menstrual bleeding over the last two years getting increasingly heavier. She was taking iron treatment for a long period and because of her conviction, she was afraid of transfusion. A PAP smear performed one year earlier was within normal limits.

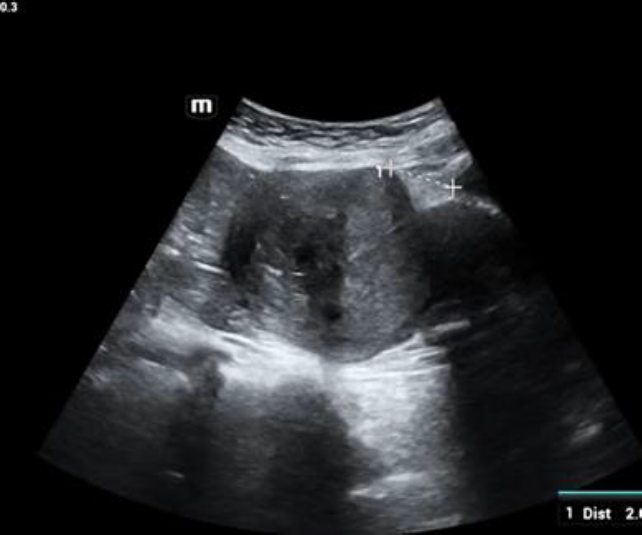

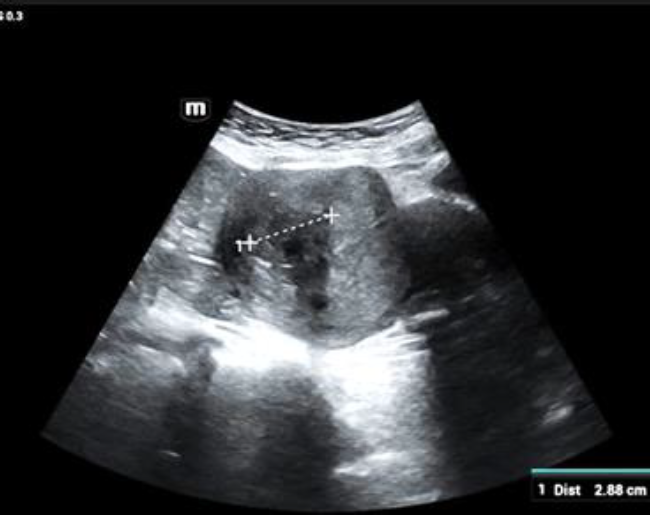

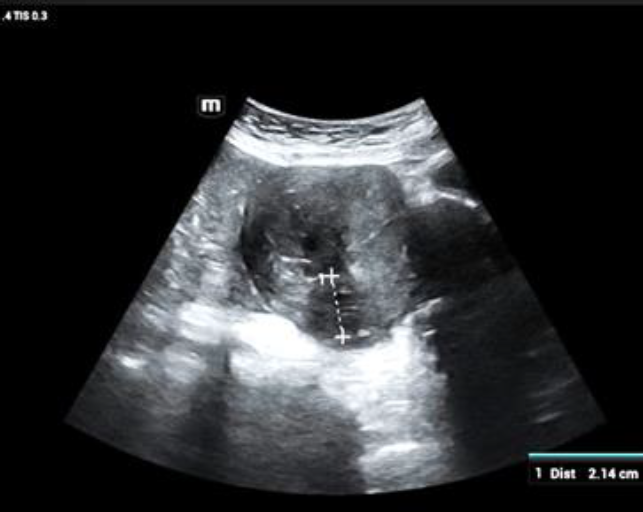

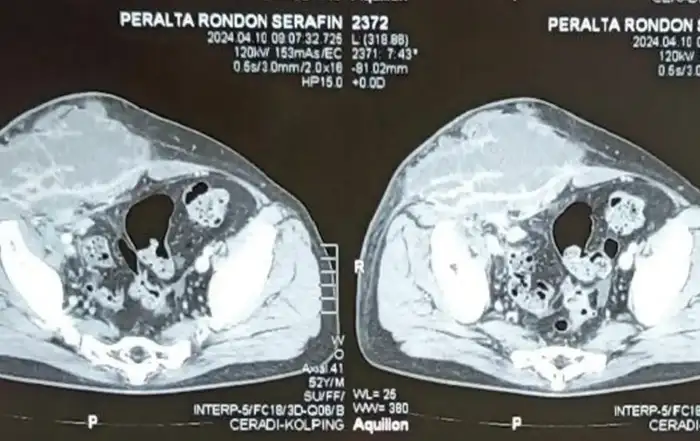

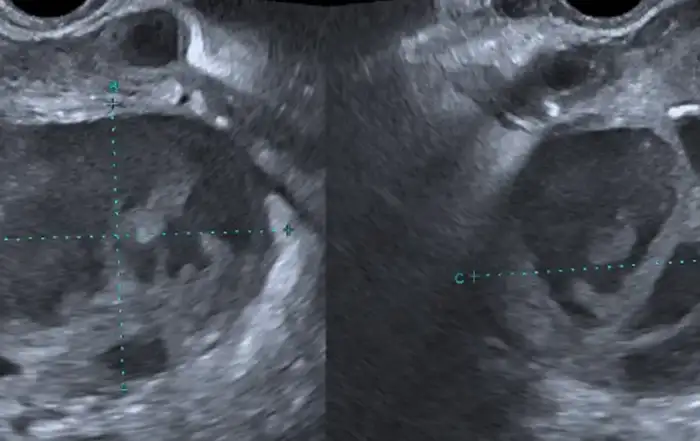

At admission, she was in good shape, normal vital signs, with palpebral conjunctiva moderately coloured. At pelvic examination, the cervix was short and highly located, the uterus was bulky with limited mobility but grossly regular on its surface. The diagnosis of uterine fibroid with haemorrhagic complication was retained with suspicion of an intrauterine fibroid. Transabdominal ultrasound showed two fibroids, one on the anterior wall, grade 2 of 2.8×2.4×2.7 cm (Fig 1.A) with a myometrial safety margin to theserosa of 0.87 cm and the other one, on theposterior wall grade 5 measuring 2.2×2.0x2.5cm (Fig 1.B). There was no isthmocele. Inaddition, the uterus was attached to theanterior abdominal wall with no spacebetween the two structures and a negativesliding sign. A 2.05 cm distance wasmeasured between the superior limit of thebladder and the inferior limit of the adherendportion of the uterus to the anteriorabdominal wall (Figure 1.C).

After counselling about hysteroscopic removal of grade 2 fibroid and the option of laparoscopic hysterectomy, the patient preferred the last option given the fact that she had no future fertility projects.

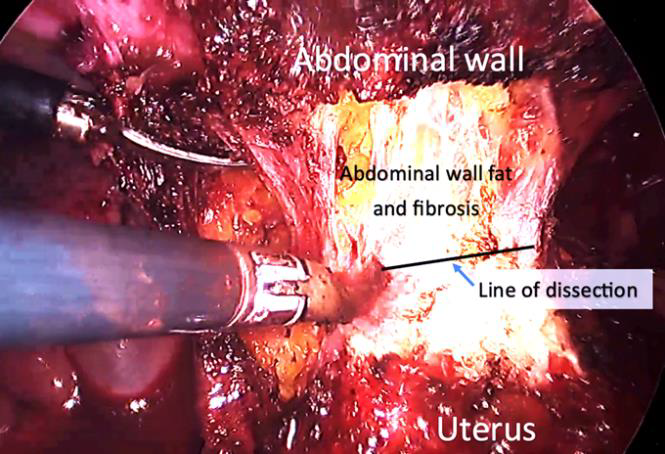

The preoperative haemoglobin was 10 gr % and the rest of the testing was normal, thereby the procedure was scheduled. Four trocars were placed: a 10 mm optic trocar at 4 cm above the umbilicus, two 5 mm left lateral and one 5 mm right lateral. The abdominal CO2 pressure was kept at 15 mm Hg. As findings, the uterus was densely adhered to the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 2) with the ovaries and the tubes normal.

The pouch of Douglas was free of adhesions. As ultrasound showed that the bladder was 2,05 cm lower down compared to the lowest inferior adherend part of the uterus, its dissection from the anterior abdominal wall was conducted without particularity leaving the fat above on the anterior abdominal wall and continuing close to the uterine wall (Figure 2).

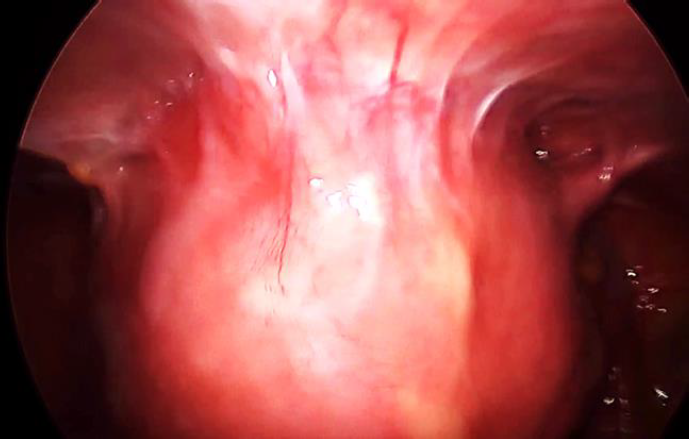

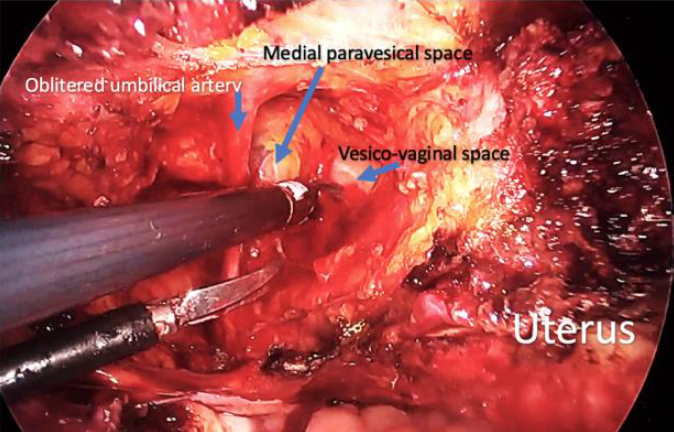

This dissection evolved concomitantly with the separation of the adnexa and the opening of the broad ligament. The bladder was partially filled with normal saline to optimize its recognition during dissection. Hysterectomy was performed using a lateral approach opening the left paravesical space (Figure 3), that allowed to enter the vesicovaginal space from the left and to dissect into this space. At that point, the left uterine artery was easily coagulated and cut and as the adhesions were situated only in the anterior aspect of the pelvis, there was no need to first isolate the ureter to secure it.

The bladder was further dissected away using the vesicovaginal space and evolving up to the right side. The procedure on the right side was uneventful as the bladder was already dissected. A colpotomy was made using monopolar energy with a L-shaped hook. All along the procedure, the manipulation of the uterus was done by a 5 mm myoma screw from the abdomen placed alternatively close to the uterine horns. At the time of colpotomy, a vaginal cup was used to delineate the vaginal wall. After its detachment, the uterus was removed vaginally. The whole dissection was conducted using a bipolar forceps and scissors. Both tubes were removed. Closure of vagina was done using a Vicryl 1 with continuous suture involving both uterosacral ligaments. The total blood loss was 20 ml and the uterus weighted 327,3 gr.

Risk factors/Mechanism of ventrofixed uterus in patient with history of Cesarian section.

The patterns of adhesions following CS vary widely from none to very dense adhesions with various associated factors (8). The most widely accepted surgery leading to a ventrofixed uterus is a CS even if other pelvic surgeries can be complicated by this condition (9). The risk of post Cesarean adhesions increases with the number of previous CS as reported in many studies, but ventrofixed uterus has been described even after only one CS indicating the existence of other factors (4, 9, 10). Among surgical factors that influence the development and extent of postoperative adhesions, the one- or two-layer closure of the uterus and closure or no closure of peritoneum have been debated (11). It has been reported that single layer closure of uterine incision was associated with more adhesions to the bladder than double layer closure. Likewise, there has been evidence that non-closure of the peritoneum during CS is associated with more adhesions compared to closure (12). In fact, it is possible that the absence of peritoneal closure on the uterus leaves uterine incisional windows, with the raw area remaining uncovered and facing the peritoneum at the level of the abdominal wound and that is ideal condition to favor adhesion formation (8, 13).

Furthermore, an excess bleeding/ooze may lead to enhance adhesion formation and create collections, secondary colonized by pathogens with localized peritonitis and subsequent fibrosis (14). Another origin of this localized peritonitis could be a post Cesarean endometritis that contaminates the pelvic cavity and concentrates on the anterior aspect.

Preparing patients and tailoring the surgery/hysterectomy

Before surgery

When preparing patients for hysterectomy or any other surgery, the surgeon should pay attention on the surgical history including the post-operative events and related late complications. Thus, patients with repeated pelvic surgeries including multiple CS, infectious complication after pelvic surgery, low pelvic pain after prior CS and infertility should be cautiously considered as being at particular risk for ventrofixed uterus (6,9).

Clinically, the cervicofundal sign described by Shesh et al. is very helpful (8). The findings are described by speculum and bimanual examination: the posterior vaginal wall is pulled upward and stretched in its upper half, if the cervix cannot be clearly visualized even after the use of an anterior vaginal wall retractor and/or vulsellum, it is high and almost behind, or close to, the pubic symphysis. Most of the time, the uterus is difficultly palpated due to the highly placed fundus and because its mobility decreases or disappears. A particular attention should be paid in cases of uterine fibroid that may induce confusing because fibroids do limit the mobility of the uterus as well. Furthermore, preferably under anesthesia just before starting surgery, the traction on the cervix or the insertion of a probe into the uterus to mobilize it backward, will dimple in or tuck in the anterior abdominal wall (6).

In practice, when the patient has a previous CS, it is better to foresee that there could be a ventrofixed, uterus adherend to the anterior wall. Ultrasound with filled bladder can help. According to the described altered ultrasound findings by Shesh et al. the cervix is elongated, easy to identify, even a full or overdistended bladder does not appear between the fundus and anterior abdominal wall, and the uterus may tend to show retroflexion with filled bladder because this later pushes the elongated cervix, but the corpus remains immobile (9).

Furthermore, ultrasound can show a fat tissue plan, if it exists, between the inferior limit of the adherend uterus and the superior limit of the bladder. This fat tissue layer can be measured to guide dissection during surgery. One should assess the bladder all along its superior limit even laterally because sometime on the median part the bladder is sufficiently down, but the lateral aspect can be attached higher. Mobilization of the uterus with the vaginal probe shows a negative sliding sign between the uterus and the anterior abdominal wall.

These evidence points of adhesions can be detected by high-resolution ultrasonography and functional MRI; both can further detect limited movement relative to one or more organs joined into the adhesions (9). However, with high-resolution ultrasonography, MRI is not compulsory, as it is more expensive and not always available in many regions of the world.

During surgery

Beyond the symptoms that can be disturbing for patients like lower chronic abdominal pain, infertility, the ventrofixed uterus may lead to uncertainty for the surgeon tackling the condition during surgery facing a prolonged operating time and the high bladder injury rate (5). It is then helpful to be aware of what can be done to reduce the rate of organs’ injury during surgery.

1.Location to introduce the Veress needleand/or the first trocar should appropriate toavoid adhesions, and the uterine funduslocated high in the abdomen and to allowbetter visualization at the starting point ofthe surgery. Most of the time, but dependingon the size of the uterus, the fundus is locatedat the halfway between the umbilicus and thepubic symphysis (9). The insertion pointmust then be either preferably higher at 4 to5 cm supraumbilical or on a left lateral point.However, attention must be paid for theplacement of the instrument trocars, becauseafter dissecting the uterus from the anteriorabdominal wall, it will drop in the pelviccavity and if trocars have been placed toohigh, instruments will struggle to reach thevaginal level especially the needle holders.Sometimes, some trocars must be replaced lower.

2.To better highlight the boundaries of thebladder, some surgeons use thecystosufflation technic (using CO2 in thebladder) or they moderately fill the bladdereither with saline solution or with saline withmethylene blue. The methylene blue has theadvantage to delineate the bladder and toimmediately show injury when it occurs.When the bladder is dissected away, it can beemptied to facilitate further steps of thesurgery especially the closure of the vagina.

3.Using retroperitoneal spaces to dissect theuterus from the abdominal wall. For everydifficult surgery in the pelvis, retroperitonealspaces are of paramount usefulness. In thecase of uterus adherend to the anteriorabdominal wall, the paravesical spaces areoften free and can be exploited for dissectingfrom the lateral aspect to the middle. Most ofthe time, one paravesical space suffices tomake the bladder dissection easy even on theopposite site. At the level where the uterus istightly adherend to the anterior wall, thesurgeon will enter the retroperitoneal spaceof the abdominal wall. He must rememberthat fat belongs to the abdominal wall andguide his dissection leaving the fat above.During dissection, it is important to keep inmind the distance between the superior limitof the bladder and the inferior limit of theadherend uterus as described by ultrasound.

4.The lateral approach to dissect the bladder.Most of the time, access to uterine vessels isno longer difficult once the paravesicalspaces are dissected. They can easily becoagulated and cut. From that step, in case ofadhesions between the bladder and thecesarean scar, the surgeon can develop thelateral approach to dissect the vesicovaginalspace, low enough, at a point where thebladder is not adherend to the uterus. Thereis always a virgin anatomical area with alveolar tissue belonging to the bladder. This area is the gateway to the virgin vesico cervical fascia over the vaginal fornix. This area can also be delineated by pushing the vaginal fornices by vaginal manipulation (swabs on a forceps). Then from bellow, the dissection of the bladder will be pursued upward and helped by the moderately filled bladder, the fibrosis between the bladder and the uterine wall will be sharply cut.

5.Filling of the bladder at the end of theprocedure to check for bladder injury in caseof doubt is mandatory because shouldbladder injury occur, recognition andimmediate repair provides a very goodprognosis.

Conclusion

Adhesions during surgery are associated with increased morbidity due to prolonged operating time and organs injuries. Their exact location is almost non predictable but for adhesions secondary to CS, the involvement of the bladder is common and increases the complexity of the procedure. Surgeons should be aware of the risk of the ventrofixed uterus and how to conduct the workup and surgery for hysterectomy in such patients using some tips and tricks developed in this paper. This could help to better counsel the patient and reduce the complication rate.

References

Fig.1: A. Fibroid FIGO grade 2, B. Fibroid FIGO grade 5, C. Distance between the superior limit of the bladder and the inferior limit of the adhered portion of the uterus, bladder moderately filled

Fig. 2a: Uterus adhered to the anterior abdominal wall.

Fig. 2b: Dissection of the uterus adherend to the anterior abdominal wall. Dissection is carried out on the line between the fat and the uterine wall

Fig. 3: Dissection of the bladder. Obliterated umbilical artery, left medial paravesical space and vesicovaginal space are shown.