Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.2025003

Abstract

This article presents two cases in which clinical and imaging findings were suggestive of pelvic inflammatory disease (pelvic abscess) but the final diagnosis revealed a pelvic malignancy. The authors reviewed all English written articles published in PubMed from January 1996 to June 2024. Current evidence does not establish pelvic inflammatory disease as a definitive risk factor for ovarian cancer. However, several studies show that postmenopausal women with pelvic inflammatory disease present a higher risk of associated malignancies. Clinical, ultrasound and intraoperative findings of a tubo-ovarian complex/abscess may mimic epithelial ovarian carcinomas and in case of surgery, particularly in postmenopausal women, intraoperative frozen section is strongly advisable. In postmenopausal women unresponsive to medical therapy, the surgical team should include at least one specialist trained in gynecologic oncology interventions.

Introduction

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an infection of the upper genital tract, including the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and often affects adjacent organs. One possible serious complication is the development of pelvic inflammatory masses that may manifest as an “agglutination” of the affected anatomical structures (tubo-ovarian complex) or a collection of pus involving infected structures (tubo-ovarian abscesses) (1). Clinical and ultrasound presentation of a tubo-ovarian abscesses can closely resemble ovarian cancer. Clinically, both can manifest with pelvic pain, adnexal mass palpable on gynecological examination and/or abdominal distension. Sonographically, both conditions can present as a multilocular or multilocular-solid, highly vascularized adnexal mass with septations and internal echoic content consistent with inflammatory debris (2,3). Additionally, an elevated cancer antigen 125 (CA125) level can be observed in both conditions (4,5).

In this article, the authors present two cases in which the clinical and imaging findings, initially indicative of PID, obscured the underlying diagnosis of ovarian cancer. An extensive review of the literature was conducted in PubMed for similar cases published in English from January 1996 to June 2024. From the 507 articles identified by using the search term combinations “pelvic inflammatory disease” AND “ovarian cancer” AND “tubo-ovarian abscess” AND “ovarian cancer” the authors selected 20 articles considered relevant for the purpose of this review.

Case Report 1

A 70-year-old nulliparous woman with a history of ovarian endometriosis, was submitted to a hysteroscopy in the context of a symptomatic endometrial polyp diagnosed by ultrasound (29 mm x 18 mm x 35 mm). Histological evaluation revealed a benign endometrial polyp.

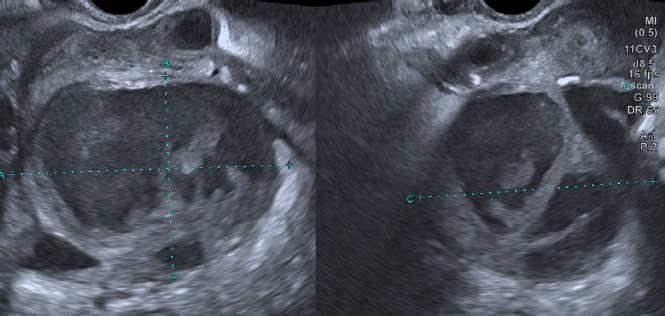

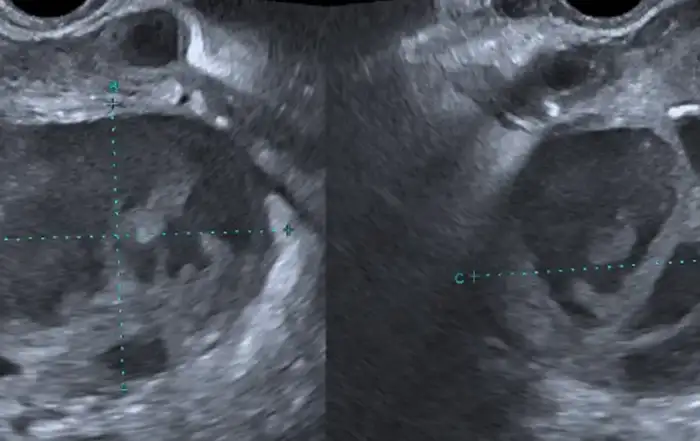

Two weeks after the procedure the patient presented in the emergency department with acute pelvic pain and fever (38.5ºC). Bimanual palpation was painful and purulent leukorrhea was evident on physical examination. Laboratory tests showed white blood cells (WBCs) count of 12,000/μl with 83% of neutrophils, C-reactive protein (CRP) 250 mg/L. Pelvic ultrasound identified an anteverted uterus, with a FIGO 2-5 posterior fibroid and endometrial polyp with 25 mm x 12 mm x 33 mm color score 3. In the left adnexal area adjacent to the uterus, a multilocular-solid cystic formation (7 locules), with “ground glass” content and a color score 3 with 84 mm x 67 mm x 70 mm was identified (Figure 1). In the retro uterine region, there was also a unilocular-solid formation with 59 mm x 61 mm x 57 mm, color score 3. None of the ovaries was equivocally identified. Due to these findings, CA125 levels were also determined with a result of 123.8 IU/ml. The patient was admitted and immediately started on intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy (ceftriaxone 1g IV daily, metronidazole 500 mg iv twice daily, and doxycycline 100 mg IV twice daily). Clinical and laboratory improvement ensued and the patient was discharged at day nine with outpatient completion of antibiotic therapy (metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily, and doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily) for 14 days.

Two months later, at a follow-up gynecology appointment, the patient complained of persistent pelvic pain. Pelvic ultrasound revealed persistence of the left adnexal multilocular cystic formation, although CA125 level had decreased (85 IU/mL). Surgical treatment was proposed and an exploratory laparotomy was performed. At inspection a retro-uterine mass of approximately 10 cm long mass was found in close contact to the left ovary. Extensive adhesiolysis, total hysterectomy, and bilateral adnexectomy were performed with incidental rupture of the left adnexal formation with exteriorization of purulent material. The final histological analysis revealed a bilateral clear cell carcinoma of the ovary with involvement of the left fallopian tube, a borderline serous-mucinous tumor of the left ovary and bilateral ovarian endometriosis. Microbiology analysis of the aspirate was negative. The patient underwent surgical staging completion (pelvic and lumbo-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy and parieto-colic gutters biopsies) with no evidence of residual disease and was staged FIGO IB and referred for follow-up at the Gynecological Oncology Unit. It has now been two years since the surgery with no evidence of disease recurrence. (Figure 1)

Case Report 2

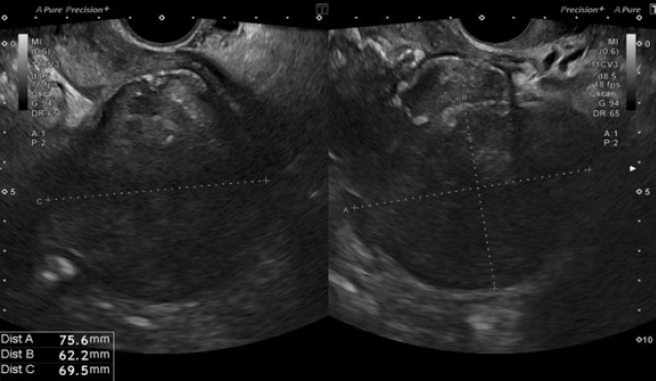

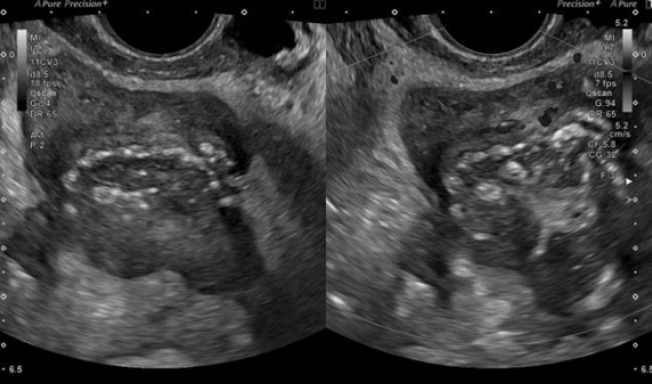

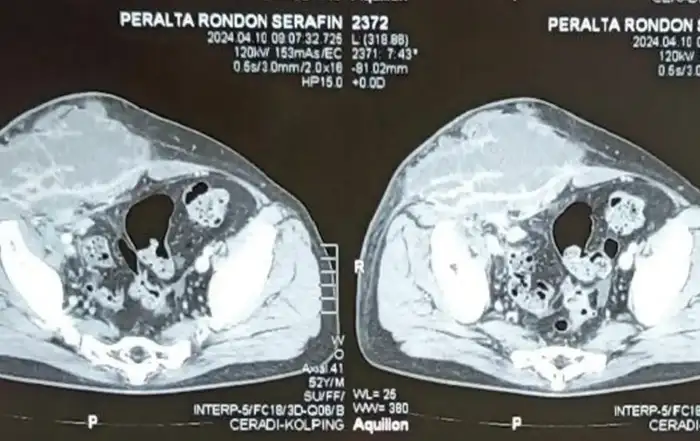

A 50-year-old nulliparous woman (menopause at the age of 39, treated with menopausal hormone therapy for five years), with a history of right adnexectomy at forty years old due to PID, presented to general emergency department with acute pelvic pain and fever (38.5ºC) for a week. She had been on ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg orally, twice day for 5 days. Laboratory tests showed increased inflammatory markers (WBCs 18,000 /μl with 77% of neutrophils; CRP 231 mg/L. An abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a septate cystic lesion in the left adnexal region with 115 mm x 80 mm x 65 mm, irregular contours, thick wall, heterogeneous content, and some calcifications. Endopelvic fluid was also observed, suggesting cyst rupture or infection. A pelvic ultrasound revealed an anteverted uterus with reduced mobility and heterogeneous myometrium suggestive of diffuse fibromatosis. Notably, there was a left posterolateral FIGO 7 nodule (Figure 2) with 76 mm x 62 mm x 70 mm (initial differential diagnosis: myoma versus solid, regular, and sparsely vascularized adnexal mass with peripheral flows). In the right ovarian fossa, an irregular unilocular formation with 44 mm x 40 mm x 41 mm, “ground glass” content, color score 2, suggestive of infectious collection (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted and initiated triple intravenous antibiotic therapy (ceftriaxone 1g IV daily, metronidazole 500 mg IV twice daily, and doxycycline 100 mg IV twice daily). Due to clinical and laboratory improvement, the patient was discharged at day six with outpatient completion of the antibiotic therapy (metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily, and doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily). However, she was readmitted two days later due to fever and worsening abdominal pain, along with increased leukocytosis (WBCs 14.000/μl) and CRP (116 mg/L).

Triple intravenous antibiotic therapy (ceftriaxone 1g IV daily, metronidazole 500 mg IV twice daily, and gentamicin 240 mg daily) was restarted, and surgical intervention planned. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. A left tubo-ovarian mass was evidenced intra- operatively. A total hysterectomy with left tubo-ovarian mass excision was performed. Histological examination revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the ovary (stage: FIGO IIB). Microbiological results were negative. The patient was referred to the Gynecological Oncology Unit. Without imaging signs of residual disease, she received six cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Currently, the patient is one year after surgery and seven months after the last cycle of chemotherapy with no evidence of disease recurrence.

Discussion

The first case describes a 70-year-old nulliparous woman with a history of ovarian endometriosis, with clinical manifestations and ultrasound findings suggestive of PID after a hysteroscopic endometrial polypectomy. Due to resistance to antibiotic therapy, surgery was performed and definitive histological diagnoses were established: bilateral ovarian clear cell carcinoma, unilateral borderline serous-mucinous tumor and bilateral ovarian endometriosis. The second case describes a 50-year-old nulliparous woman with a history of right adnexectomy for PID, with clinical manifestations and ultrasound findings suggestive of PID. After failure of antibiotic therapy, surgical exploration revealed a lesion whose definitive diagnosis was ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

In both cases, the patients presented with the risk factors of PID as well as the clinical features and ultrasound findings compatible with PID (pelvic abscesses). However, after surgery, the histological diagnosis revealed ovarian malignant neoplasms. These two situations, that were witnessed over the past 2 years, prompted to evaluate our clinical practice and analyze the available literature on the clinical and ultrasound overlap between PID and adnexal malignancy.

A non-systematic but comprehensive literature search was conducted of the PUBMED database, as described above. Current literature does not establish PID as a definitive risk factor for ovarian cancer (6). Nevertheless, some studies have suggested a potential association (5, 7, 8, 9, 10). Although this relationship may not be causal, several studies do show that postmenopausal women with PID are at higher risk of associated malignancies (11, 12, 13). Identifying a tubo-ovarian abscess in a postmenopausal woman is less common and may obscure significant underlying health issues (14). Gynecological cancers that were found to be reported in association with PID include cervical squamous cell carcinoma, epithelial ovarian carcinoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma (11, 12, 13, 15).

The clinical characteristics and ultrasound findings of a tubo-ovarian complex or a tubo- ovarian abscess can closely mimic those seen in epithelial ovarian cancer, including mucinous, serous, clear cell and endometrioid subtypes. It has been documented that PID, when complicated by the development of an abscess, may present sonographically as a unilocular or multilocular mass exhibiting a cogwheel appearance (in a component corresponding to the still visible sactosalpinx with incomplete septa) and mixed echogenicity (16). Abundantly vascularized solid component may be observed; thus, unilocular-solid or multilocular-solid presentation of a pelvic abscess can be seen. Borderline mucinous tumors of the ovary typically appear on ultrasound as unilateral, multilocular cystic masses with more than ten locules and no clearly defined solid components (16, 17). In contrast, invasive mucinous tumors often present with prominent solid areas (17). The most characteristic ultrasound feature of borderline serous ovarian tumors is the presence of papillary projections, distinguishing them from invasive serous tumors, which usually show fewer papillary structures but contain solid components (18). Clear cell carcinomas develop from endometriotic nodules in approximately 20-30% of cases with this diagnosis. Their most distinctive ultrasound features include solid multilocular or unilocular masses, often with low-level internal echoes or a ground-glass appearance. Additionally, solid nodules and papillary projections are seen in about 38% of cases, providing further diagnostic insight (19). Due to these similarities, concomitant pelvic malignancy should always be ruled out, in particular in postmenopausal PID resistant to intravenous antibiotic therapy. When ultrasound findings are inconclusive, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable modality for a comprehensive investigation of the differential diagnoses. However, even with a thorough pre- and intra-operative investigation, concomitant malignancy can be unrecognized (13). In these situations, the surgical threshold should be lower (20, 21). In cases of postmenopausal tubo-ovarian abscess that does not respond to medical therapy and requires a surgical intervention, we recommend involving at least one specialist in gynecological oncology as part of the surgical team. Additionally, considering intraoperative frozen section is strongly advisable.

Conclusion

Prospective studies are needed to establish PID as a risk factor for ovarian cancer. PID is less frequent in postmenopausal than in premenopausal women, while the prevalence of ovarian cancer increases with age. If there is an inadequate response to conservative (antibiotic) therapy, in all patients and especially in postmenopausal women with persistent symptoms, a persistent adnexal mass or an adnexal lesion whose morphological complexity is increasing, it is crucial to exclude preoperatively accompanying neoplastic pathologies. Despite all efforts, distinguishing between these conditions can be very challenging due to significant clinical and imaging overlap.

References

Figure 1. Case 1: Left adnexal multilocular-solid formation with “ground glass” content, interpreted as an infectious tubo-ovarian complex.

Figure 2. Case 2: Left posterolateral FIGO 7 myoma.

Figure 3. Case 2: Right adnexal unilocular and irregular formation with “ground glass” content, interpreted as an infectious collection.