Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar5.2024024

Abstract

Uterine rupture with bowel incarceration after dilatation & curettage (D&C) is a rare clinical condition. Although there are risk factors such as increased intra-abdominal pressure, history of pelvic infection, history of pelvic surgery, or uterine anomalies, no risk factor may be detected in most cases.

Cases with abdominal pain and bleeding after uterine manipulation should suggest uterine perforation. Some cases may be asymptomatic and may be detected incidentally on imaging. Herniation or incarceration of intestines and other intra-abdominal structures from the perforated area are rare but may cause serious clinical conditions depending on the degree and location of the hernia.

Introduction

Uterine perforation of the uterus may result in considerable morbidity and mortality. These outcomes are valid for both gravid and non-gravid uteruses. D&C is the most commonly used procedure for surgical termination of pregnancy and biopsy goals in a variety of gynecological conditions. It is well known that any intrauterine procedure, from a simple aspiration to a more complicated curettage, carries the risk of uterine perforation (1). Diagnostic and therapeutic indications for D&C outside of obstetrics include a wide range of diseases accompanied by abnormal uterine bleeding, such as endometrial hyperplasia, prolonged heavy menstrual bleeding, or postmenopausal bleeding (2) Uterine perforation following D&C may affect intraabdominal structures/organs and their possible involvement or retraction into the uterine cavity (3–6). Damage to surrounding organs can sometimes lead to emergencies requiring immediate medical attention, threatening the patient’s life. One of the rarest but still possible complications is the incarceration of the colon or other intestinal structures in the uterine cavity following uterine perforation during an intrauterine procedure. The symptomatology accompanying this condition is nonspecific and sometimes vague. The timing of a correct diagnosis sometimes varies from a few hours to several years from the time of the initial maneuver. To our knowledge, no case of uterine perforation after a surgical procedure with appendix epiploic and colon incarceration has been reported yet. The purpose of the current study is to examine the process, clinical presentation, imaging examination, and timing from D&C to the correct diagnosis of uterine perforation with appendix epiploic and colon incarceration and to evaluate its impact on women’s health.

Case report

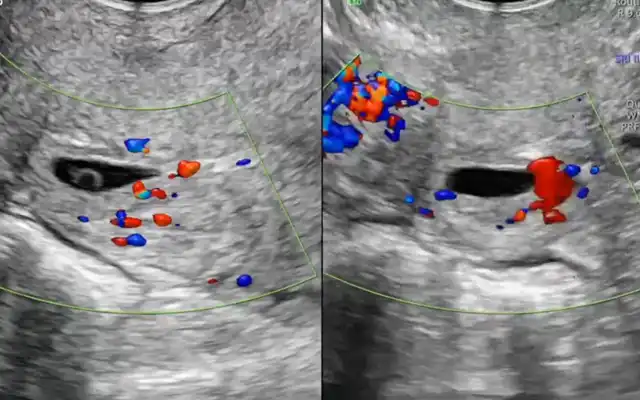

A 39-year-old woman came to the clinic with a complaint of menstrual delay. An intrauterine pregnancy of 5 weeks + 5 days was detected by transvaginal ultrasonography. The cavity had irregular borders, but a positive fetal heartbeat was observed. Pregnancy was confirmed with beta hCG test. At the request of the patient and her husband, D&C was performed due to unplanned pregnancy.

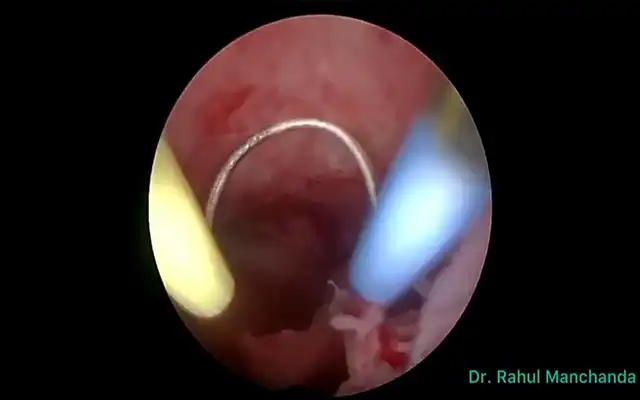

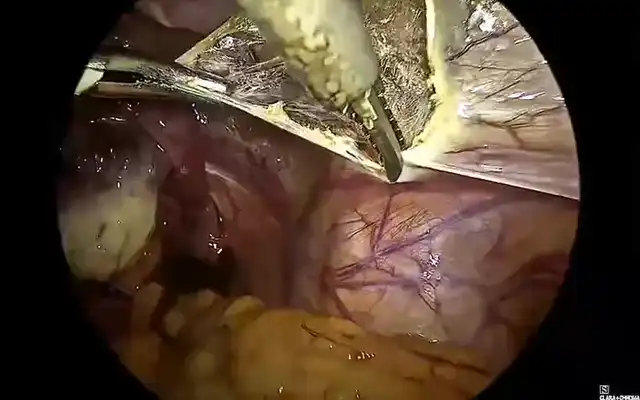

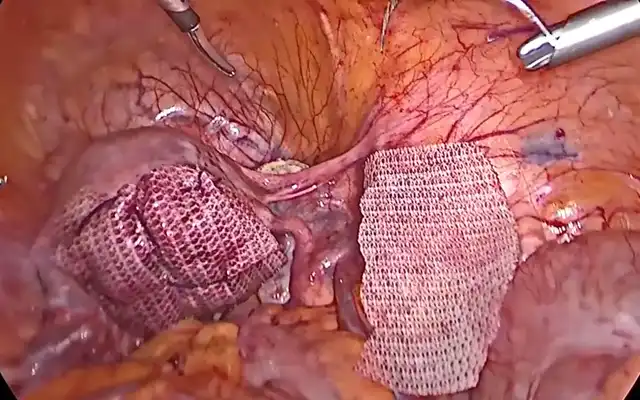

The patient was scheduled for follow-up and control after one week. While no intrauterine images of retained products of conception were observed at ultrasonography, a polypoid lesion of approximately 1.5 cm was detected at the fundus level. There were no symptoms or additional findings at examination. The patient’s medical history did reveal, that an endometrial sampling was performed in another center approximately four months prior due to abnormal uterine bleeding and histopathological diagnosed as caused by an endometrial polyp. During this period, the patient refused the hysteroscopic examination recommended to clarify the diagnosis. One week after the last check-up, she came to our clinic again for an intrauterine device (IUCD) containing levonorgestrel in view of her request for contraception and a history of abnormal uterine bleeding. Her medical state was fine, a body mass index of 22 was noted and she was a non- smoker. Her vital signs were normal, with a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, a heart rate of 90 beats per minute, and there was no abdominal distension or tenderness during the clinical examination of the abdomen. While there were no abnormal findings in the pre-procedural examination, there was a polypoid lesion around 1.5-2 cm at the fundal level at ultrasound. An ultrasonographic check was performed again one week after the IUCD was inserted into the patient, and no intrauterine device was observed in the uterine cavity, and no thread of the device was observed in the cervix at vaginal examination. By direct radiography, a density corresponding with the intrauterine device was present in the abdomen at the level of the pelvis. The decision was made to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy with the preliminary diagnosis of an IUCD migrating into the abdomen. At the same time, bilateral tubal ligation was planned, upon request, for sterilization. During surgery, there was a dense intestinal adhesion of around 2-3 cm at the level of the uterine fundus. When the lesion was approached, it was observed that a segment of the intestine was attached to the uterus and further incarcerated into the uterus. The incarceration of the epiploic of the appendix was confirmed as a string of fibro-lipomatous appearance running from the uterine fundus. With the help of bipolar coagulation and dissection, the incarcerated large colon segment was removed from the perforated area. At first dissection with cold scissors was tried, but the herniated tissue was larger in diameter as compared to the perforated area, so switched to thermal dissection was preferred, foreseeing that tissues could be traumatized and even teared due to traction. The proximal part of the ascending segment and the bowel loop in the same region were inflamed and edematous. The perforated uterine area was closed with absorbable suture. The procedure was terminated after observing the uterus and colon for a while. The patient was discharged in good condition after gas and stool discharge were observed on the first postoperative day. The patient was checked again after 1 week and her general condition was good, and she did not have any active complaints.

Discussion

Uterine perforation is a likely complication of the intrauterine maneuvers used for evacuation or sampling of the endometrial cavity. Although rare, it may determine immediate or distant severe results for the patient’s health. There is a constant danger of iatrogenic trauma on the posterior fundal (in sometimes even lateral wall) of the uterine cavity. This trauma can happen any time that we use intrauterine instruments; there are two types of perforations: the ones that have been caused by cervical dilation and the ones that are secondary to the progression of sharp or blunt instruments, such as blunt curettes. The risk of bleeding depends on the anatomical location, more important if vessels have been involved, the instrument used (sharp, blunt, or with energy), and the intensity of the manipulation by the surgeon. It is crucial to understand that in some cases, perforation can lead to a significant bleeding and the urgent need for surgical stitching or repair under laparoscopic control. In addition, this iatrogenic condition, defined as a perforation and local destruction of the entire uterine wall, can compromise future fertility. Uterine perforation has been reported to be more frequent, secondary to an obstetric D&C. It can also occur in cases where a non-obstetric D&C or vacuum aspiration was applied. Uterine rupture usually indicates an injury of the uterine wall secondary to an iatrogenic insult. Perforation is believed to be severe and life-threatening if it leads to immediate heavy bleeding. Therefore, uterine perforation should be suspected in the presence of bleeding during or after D&C. A possible myometrial trauma or increased inflammation after the first curettage may have facilitated perforation with the second curettage. In addition, in the case presented a polypoid lesion present during the insertion of IUCD is a clear indicator that a possible cavitary herniation occurred after the first or second curettage.

The confirmed incidence of uterine perforation with omentum incarceration is unidentified and most probably higher than published. Because instrumental uterine perforation is rare, an unknown number of cases are not documented in the medical literature. Immediate intervention is crucial in complicated uterine perforations, unknown perforations without additional complications and investigations, and pre- hospital mortality in very low-income countries (1) Some risk factors have been reported that can contribute to the occurrence of uterine perforation: complicated dilation of the cervix (primiparous or menopause), scarred cervix after surgical maneuvers or previous vaginal deliveries, malposition of the uterus, leiomyoma, adhesions, previous injury to the uterine wall, Cesarean section scar, conditions that diminish myometrial strength such as pregnancy, especially multiparity, uterine infections, advanced age, connective tissue disorders such as Ehler-Danlos syndrome, and the use of general anesthesia (7). The pelvic structures that can herniate into the uterine cavity are the omentum, the appendix, the small bowel, the ovary, or the fallopian tube (1,8–10)

Experienced clinicians suspect uterine perforation because of loss of resistance during instrument advancement. The diagnosis of uterine perforation may be suspected clinically if the patient presents with acute abdominal pain, heavy vaginal bleeding, or any signs of internal bleeding such as hypotension or tachycardia. Peritoneal free fluid may be detected by ultrasound. In rare cases, omental or bowel compression may occur. There are no reports of specific symptoms that would alert to the possible diagnosis of uterine perforation in association with these compressions.

The complete diagnosis of uterine perforation with organ incarceration should combine a detailed medical history with a thorough clinical examination and imaging evaluation, primarily using ultrasound evaluation. However, it should not exclude computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or radiographic evaluation. Abdominal X-ray is used to show hydro-aerial levels. Ultrasound has been the preferred initial imaging modality because it is readily available, affordable, does not involve ionizing radiation, and compact mobile machines can be used at the patient’s bedside or in the operating room.

The transvaginal approach better evaluates the reproductive organs by locating the perforation site. In contrast, the transabdominal approach provides a broader view of the patient’s condition, including estimating the volume of potentially associated hemoperitoneum. If ultrasound is negative or inconclusive, CT may be an additional imaging modality that allows visualization of all abdominal pelvic organs and the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum. The fatty nature of the bowel mesentery can be well detected on CT (4,11–13). Surgery is the usual treatment for intestinal incarceration. The management of uterine perforations after intrauterine interventions is not standardized, with either conservative or interventional approaches. If the patient is stable and asymptomatic, observation with close monitoring may be an option. Some units support systematic exploratory laparoscopy.

Minimal perforations without bleeding may require no intervention, while extensive and hemorrhagic perforations can be managed by bipolar coagulation or suturing. The role of laparoscopy is valuable for rapid resolution and fewer complications if the team is compatible. Since the surgery we performed is a uterine and ovarian-protective intervention, the patient’s future fertility will not be affected. Of course, since there is no colonic lumen intervention, no adverse bowel dysfunction was experienced in the early period and at the moment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, laparoscopic exploration is the preferred method in the management of a patient with uterine perforation after D&C. Suturing of the perforated scar should be performed deep into the myometrium to stop the bleeding. Complications of uterine perforation can threaten the patient’s life. It is important to note that while rare, intestinal incarceration is an exceptional but surgically critical complication. The surgeon’s experience is crucial in preventing such complications.