Authors / metadata

DOI : 10.36205/trocar3.2023003

Abstract

Vaginal ulcers can occur due to various causes such as infections, aphthous ulcers, malignancy, post- radiation therapy, or autoimmune disorders like Behcet syndrome or can be due to rare entities which may cause diagnostic confusion. We present an unusual case of vaginal ulcer in a post-hysterectomy patient presenting with vaginal bleeding. There are very few cases reported in the literature of vaginal ulcers in this context. Diagnosis is made only by excluding other common causes of genital ulcers. To the best of our knowledge, vaginoscopic pictures of vaginal ulcers are not available in the literature, not to mention lack of scientific data to support physicians in establishing the correct etiologic diagnosis. This case-report aims at demonstrating the pathology by vaginoscopy as well as providing a review on the various conditions causing it.

Introduction

Vaginal ulcers are breaks in the mucous membranes of the vagina that can cause symptoms such as itching, pain, bleeding upon touch, or the production of discharge. However, they can also be asymptomatic. Genital ulcers can be single or multiple and may be painful or painless Dryness, scaling, and excoriations preceding the ulceration suggest dermatitis.

Recurrent ulcers may indicate conditions like herpes simplex virus (HSV), Behçet disease, or fixed drug eruption. Inguinal lymphadenopathy suggests a likely infection, while uveitis, arthritis, and a family history of these conditions may indicate Behçet disease. The appearance of new ulcers after taking certain medications suggests a fixed drug eruption. Oral mucosal involvement is seen in aphthosis. Dysuria may be caused by the location of the ulcer or sexually transmitted urethritis. Constitutional symptoms (generalized symptoms affecting the whole body) can occur in conditions such as herpes simplex, secondary syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), and s ystemic lupus erythematosus.

Non sexually acquired genital ulceration (NSAGU) refers to ulcers that do not have an identifiable cause based on clinical, histopathologic, serologic, and microbiologic findings. However, Epstein Barr virus (EBV) has rarely b een identified in the base of the ulcer (1 4). NSAGU is characterized by sudden painful genital ulceration and is often misdiagnosed as a sexually transmitted infection, leading to unnecessary investigations.

It may be considered a variant of complex aphth osis or a separate condition. The onset of NSAGU may be preceded by an acute systemic illness. It is often under recognized by healthcare providers, and its underlying causes are not fully understood (1 4). NSAGU is a benign condition that can present as an acute or recurrent event but does not progress. Currently, there are no consistent treatment protocols described for NSAGU.

Case report

This is a case report of a 56 year old woman, gravid one para one, with a medical history of a total abdo minal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo oophorectomy performed 14 years before for adenomyosis and severe endometriosis. Post operative period then was uneventful and she was put on leuprolide injections for 3 months post operatively. She visited the out patient clinic with a complaint of a 3 days ongoing vaginal bleeding, without associated pain. There was no history of vaginal discharge or itching in the perineal region, nor oral aphthous ulcers or any other significant diseases. The patient was not sexually active and also reported a medical history of multiple arthralgia, for which she had received some allied medicine.

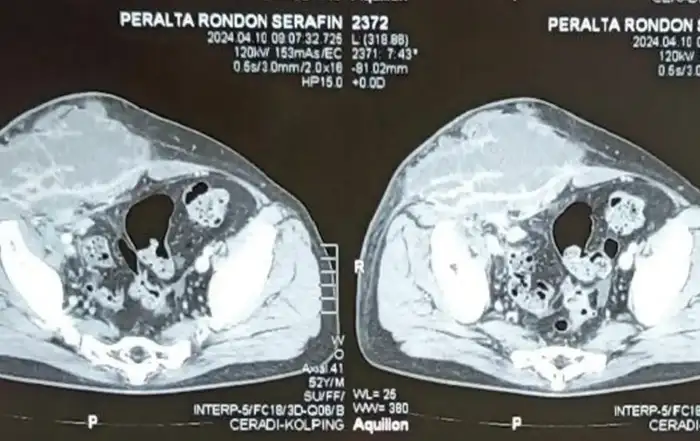

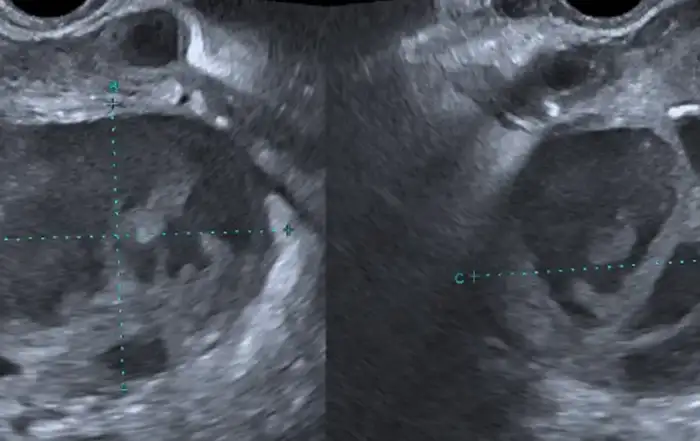

The patient was admitted and examined under anesthesia. Diagnostic vaginoscopic technique was performed using a 2.9 mm office Bettocchi hysteroscope with outflow and inflow sheaths mounted. The distending medium was normal and a Karl Storz SPIES camera wit h spectra A filter was used to evaluate the vascularity (Karl Storz Se & Co KG Tuttlingen Germany). Three punched out ulcers on the posterior vaginal wall were revealed, measuring 2×1 cm, 3×2 cm, and 2×2 cm, with a healthy vault (fig 1 2).

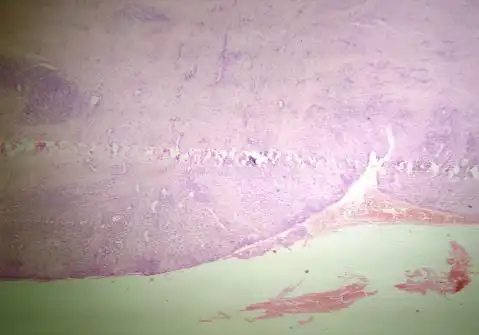

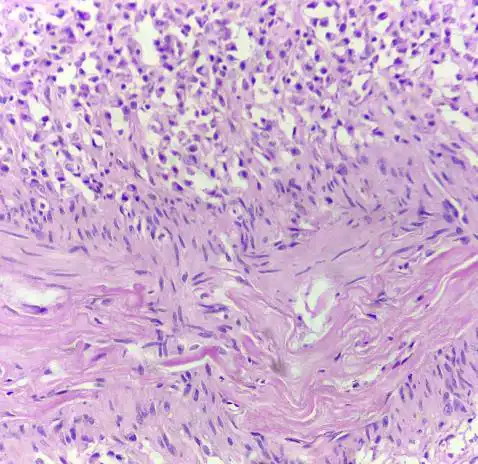

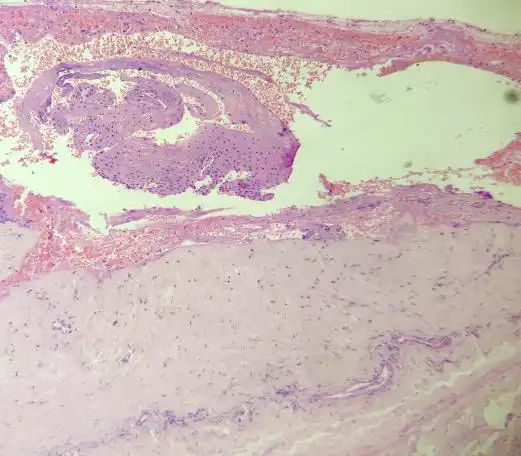

Measurements were estimated by comparison with the distance separating the tips of the open jaws of the five French grasping forceps which is about six mm. Biopsies were taken from the lower ulcer margins, and the ulcer bed was subsequently sutured to allow for hemostasis. Histologic examination of the vaginal ulceration showed active chronic inflammatory granulation tissue and fibrosis with the defect partia lly reaching the muscularis. Deeper tissues exhibited fibrosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, without evidence of vasculitis (Fig 3-5). The diagnosis of benign inflammatory ulcer was thus confirmed.

Tests for chronic inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease) and Behcet disease were performed and came back negative. (Ziel- Neelsen (ZN) stain for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain for fungal infection were also negative. No microorganisms were found or cultured.

The prescribed treatment consisted of

- Oral cefuroxim axetil 500 mg twice a day for 7 days.

- Oral metronidazole 400 mg three times a day for 7 days

- Ibuprofen 400 mg is association with paracetamol 325 mg trice a day for 3 days

- Pantoprazole 40 mg twice a day for 7 days.

The follow up was done on days three, seven, 14 and 30. The ulcers did heal well with the alleviation od the symptoms and restitutio ad integrum was witnessed by vaginal examination within two weeks. The vaginal bleeding did stop right after the suturing. The patient did respond well to the treatment.

Discussion

In a discussion about this rare case, the lack of literature on vaginal ulcers is considerable. Several conditions need to be considered in the process of differential diagnosis. The patient has presented with acute genital ulceration. Several possible causes have been considered and ruled out based on clinical features and laboratory tests. Excoriations, trauma-induced ulcers, are unlikely due to the normal surrounding skin and absence of a history of trauma. Genital herpes, characterized by small vesicles that quickly rupture into shallow erosions, is unlikely due to the absence of typical prodromal symptoms and vesicles. Primary syphilis is also improbable as the ulcer associated with it is typically painless, has a clean base, and shows little to no pus or crust. Moreover, laboratory test for syphilis was negative.

Behçet’s syndrome, a multisystem disease with aphthous ulceration, is highly unlikely given the absence of ocular or systemic complaints (5) and negative lab tests for the syndrome. Crohn’s disease, which can manifest with aphthous ulcers, is improbable as the patient has had a single episode of genital ulceration without other bowel or bladder complaints. Crohn’s disease can affect the skin with or without bowel involvement, and vulval oedema may accompany ulceration in addition to typical sinuses and fistulae (6).

Squamous cell carcinoma and vulval intraepithelial neoplasia are unlikely due to the acute nature of the ulceration, and histopathology reports are suggestive of inflammatory lesions without any premalignant features (fig 3-5).

The most probable diagnosis is NSAGU, a benign condition with an unknown cause. Episodes are often triggered by viral infections, particularly when there is viral prodrome (1-4). However, no cause has been clearly identified in patients with recurrent ulcers who do not have an underlying condition such as Crohn’s disease or Behçet’s syndrome. NSAGU ulcers share characteristics with oral aphthous ulcers, being painful and sharply marginated (punched out).

The authors would like to highlight the clarity of the vision at vaginoscopic examination with the hysteroscope, to the best of our knowledge these pictures are not available anywhere in the literature. The clarity of the layers of the vagina and of the vascularity is clearly shown. These pictures can hopefully help researchers, who are looking at treating vaginal ulcers and similar pathology, in the future.

Investigations

The diagnosis of NSAGU relies on clinical observations. However, conducting a skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis can be distressing for the patient and may yield non-conclusive results. It is crucial to investigate the presence of primary herpes simplex virus and secondary bacterial infection. This investigation should involve obtaining skin swabs for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and culture. In an emergency situation, it is essential to identify aphthous ulceration. Therefore, investigations are necessary to rule out alternative causes of genital ulceration. Biopsies from ulcers are needed to exclude malignancies.

Management

The management of NSAGU varies depending on the severity, and there are no formal treatment guidelines. For mild cases, the primary approach involves avoiding irritants such as tight clothing, perfumed soaps, pads, and liners. Analgesia and topical treatments are also recommended. Corticosteroids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, can be beneficial. Potent topical corticosteroids are generally safe to use, and when applied in an ointment form for a short duration (two weeks or less), they do not cause side effects.

In our specific case involving a patient experiencing vaginal bleeding, the management included operative vaginoscopy with biopsy and suturing of the ulcer base. This procedure helped relieve the patient’s symptoms. Additionally, prophylactic antibiotics were effective in controlling secondary bacterial infection and flare-ups.

Conclusion

There are various types of lesions that can occur in the vaginal and vulvar regions. The approach to diagnosing these lesions depends on the underlying cause. In this particular case, the diagnosis was made by ruling out known causes. When evaluating patients with such lesions, it is important to inquire about other systemic illnesses, paying close attention to symptoms related to the eyes, nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system. A comprehensive physical examination, including the examination of oral and skin lesions, should be conducted by the physician. The latter should then make a differential diagnosis and implement a multidisciplinary treatment approach for the patient.

References

Figure 1 2. Vaginoscopic picture of ulcers ( fig 1 natural aspect – fig 2 SPIES appearance)

Figure 1 2. Vaginoscopic picture of ulcers ( fig 1 natural aspect – fig 2 SPIES appearance)

Figure 3. focus of the ulceration

Figure 4. Deeper tissue reveals perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (high power)

Fig 5 Deeper tissue reveals perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (low power)