Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar1.2023011

Abstract

In this article we aimed to assess the role of diagnostic hysteroscopy in intra uterine adhesions. It is challenging to diagnose the severity of the disease in order to provide the effective treatment in cases with menstrual disturbances like hypomenorrhea and amenorrhea and infertility issues.

Methods and Outcome: In this article we provide a non-systematic review on the role of diagnostic hysteroscopy in evaluation of intra uterine adhesion and discuss it in detail. Hysteroscopy being the gold standard diagnostic and therapeutic modality for intra uterine adhesions outweighs the other modalities like hysterosalpingography, transvaginal ultrasound, sono-hysterography and MRI. Also, there are various hysteroscopy-based classification systems available which have been discussed in chronological order. The American Fertility Society (AFS) classification which includes clinical picture along with hysteroscopic findings is by far most widely accepted among various classification systems.

Conclusion: Hysteroscopy is by far the best diagnostic tool to diagnose the intra uterine adhesions and also to assess its severity in the real time. The diagnosis and treatment can be provided in the same setting with this cost-effective and time saving procedure.

Introduction

Intra Uterine adhesions (IUAs) designate bands that are formed inside the uterine cavity and maybe due to a multitude of causes. Following any uterine procedure, fibrous bands that are formed in the endometrial cavity, are termed as IUAs It can be in the form of thin strings of tissue or it can be so severe that it may obliterate the uterine cavity completely. Infertility, menstrual abnormalities, recurrent miscarriages, and lower abdominal pain are its clinical sequelae. H. Fritsch in 1894 first described amenorrhea linked with IUA in a woman who underwent postpartum curettage [1]. Later, J.G. Asherman in 1948 and 1950 published two such reports [2,3] on the etiology and the frequency of intrauterine adhesions and since then the term Asherman’s syndrome has been used, oftentimes improperly and interchangeably with IUA. However, it is important to highlight the clear distinction that Asherman syndrome is only about the severe IUAs subsequent to pregnancy-related trauma. All other cases come under the broader term of Intrauterine Adhesions [4]. The presenting symptoms associated with IUA (also known as synechiae) are usually infertility, menstrual abnormality, recurrent pregnancy losses, or abnormal placental attachment [5,6].

Among women with intrauterine adhesions, the most common symptom is infertility, affecting approximately 43% [5,7]. Menstrual disturbances like amenorrhea and hypomenorrhoea are also common presentation, nonetheless the term Asherman’s syndrome is technically interchangeable with secondary amenorrhea [5,7]. Women having intrauterine adhesions accounts for 14% chances of having recurrent pregnancy loss. Disorders of placental attachment such as placenta previa and accreta are comparatively rare (1%) [5,7].

It has always been challenging to make the diagnosis of IUAs and Asherman’s syndrome [8,9]. Recently, the advent of various diagnostic modalities and increased consciousness of the condition have directed towards a more definitive diagnosis and management of this condition [10]. Hysteroscopy is presently the gold standard diagnostic and therapeutic modality for the IUAs, as it provides clear view of the uterine cavity without any abdominal incision [11-14]. In this article we shall be reviewing various articles on the role of diagnostic hysteroscopy in evaluation of IUA and discuss it in detail.

Material Method

In this article we provide a non-systematic review on the role of diagnostic hysteroscopy in evaluation of intra uterine adhesion and discuss it in detail. Hysteroscopy being the gold standard diagnostic and therapeutic modality for intra uterine adhesions outweighs the other modalities like hysterosalpingography, transvaginal ultrasound, sono-hysterography and MRI. Also, there are various hysteroscopy-based classification systems available which have been discussed in chronological order. The American Fertility Society (AFS) classification which includes clinical picture along with hysteroscopic findings is by far most widely accepted among various classification systems.

Results and discussion

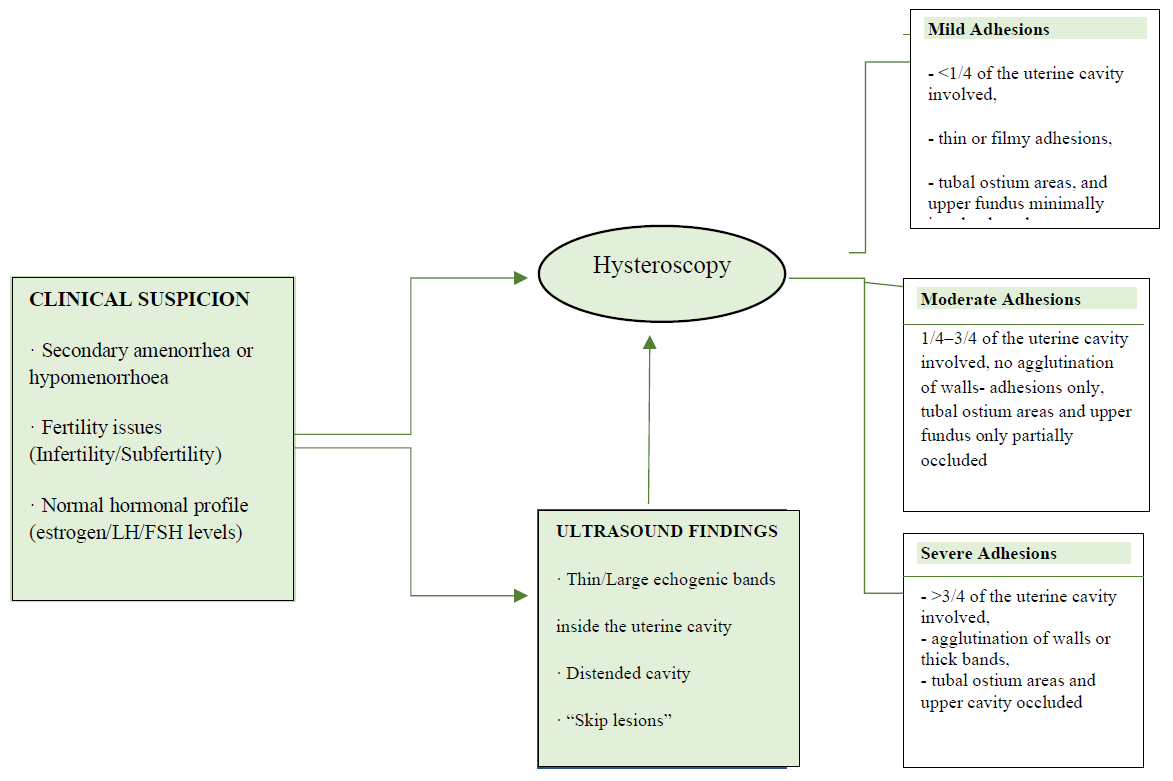

However, the correct diagnostic scheme (Figure 1)for IUAs should begin from clinical suspicionand ultrasound imaging and, consequently, confirmed with hysteroscopy, or other modalities such as hysterosalpingography (HSG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or sonohysterography (SHG) where hysteroscopy facilities are not available [8].

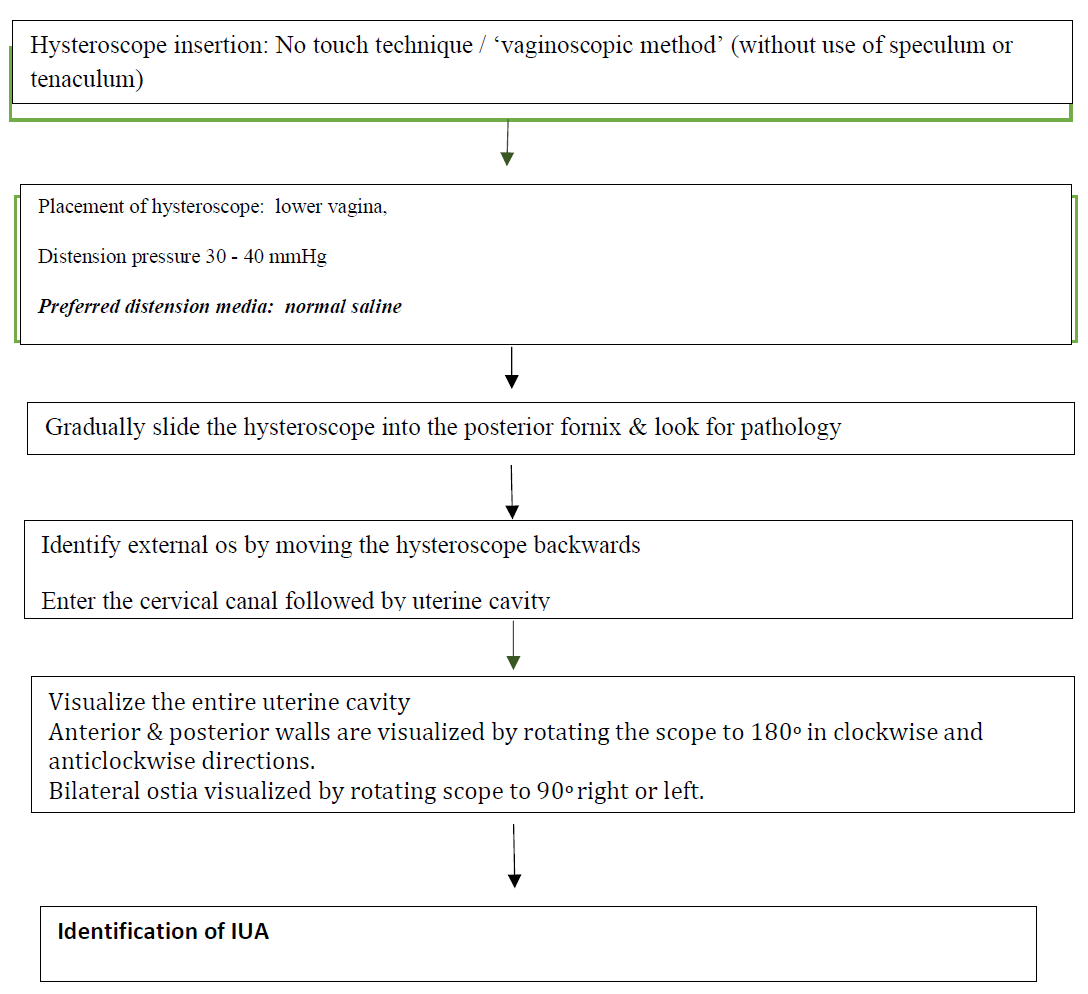

Vaginoscopic method introduced by Stefano Bettocchi in the year 1997 is a no touch technique, which is a preferred technique these days as it has various advantages as compared to the conventional hysteroscopy (steps depicted in Figure 2).

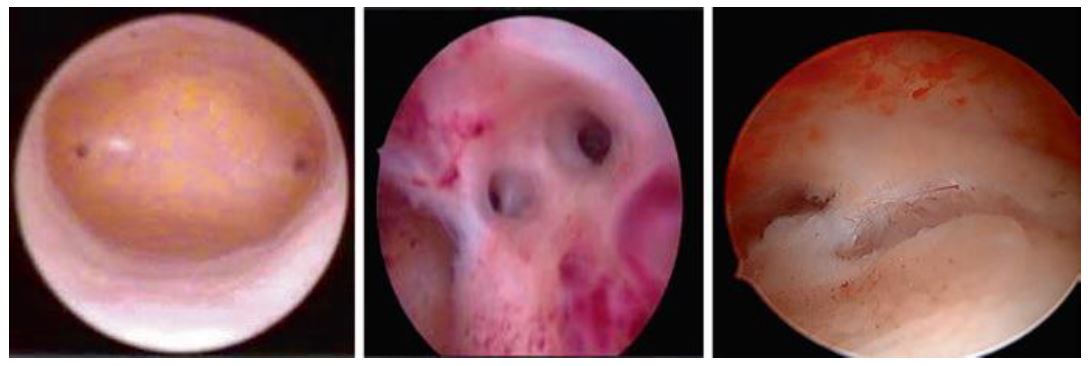

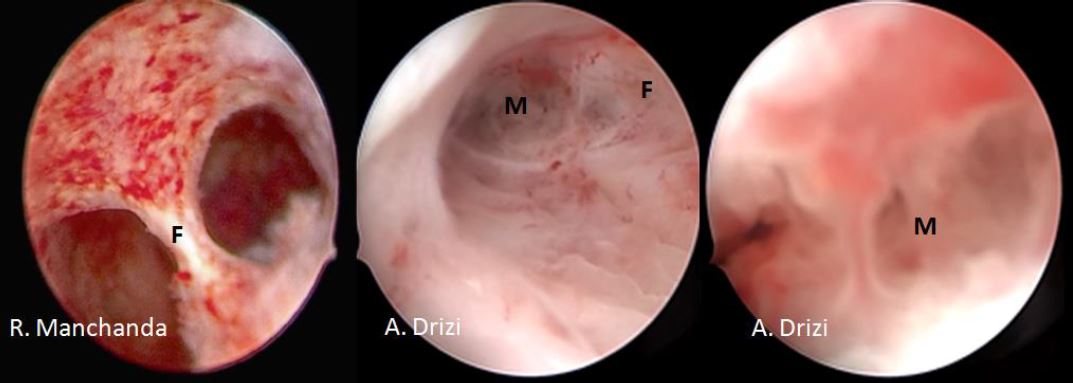

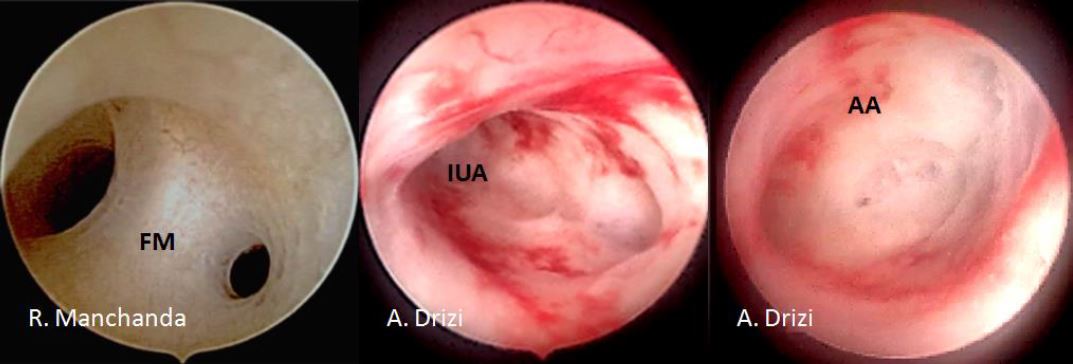

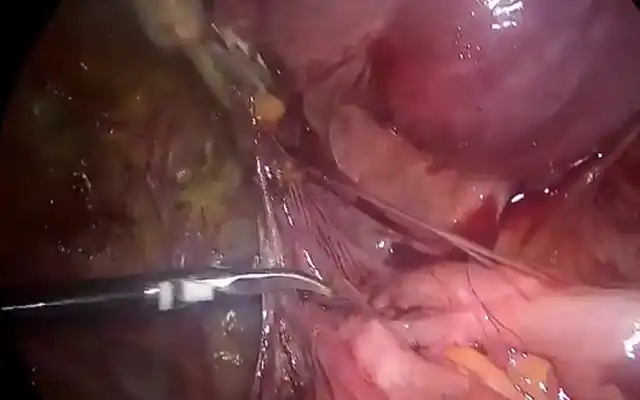

Hysteroscopy is an excellent tool to identify the intrauterine adhesions and to assess its severity as depicted in figures 3, 4, 5. Prognosis can also be assessed by evaluating the proportion of healthy endometrial tissue. Intravaginal Misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) may be given a night before the procedure in a few selected cases with cervical stenosis to ensure an easy dilatation of cervical canal [15,16].

Classification systems

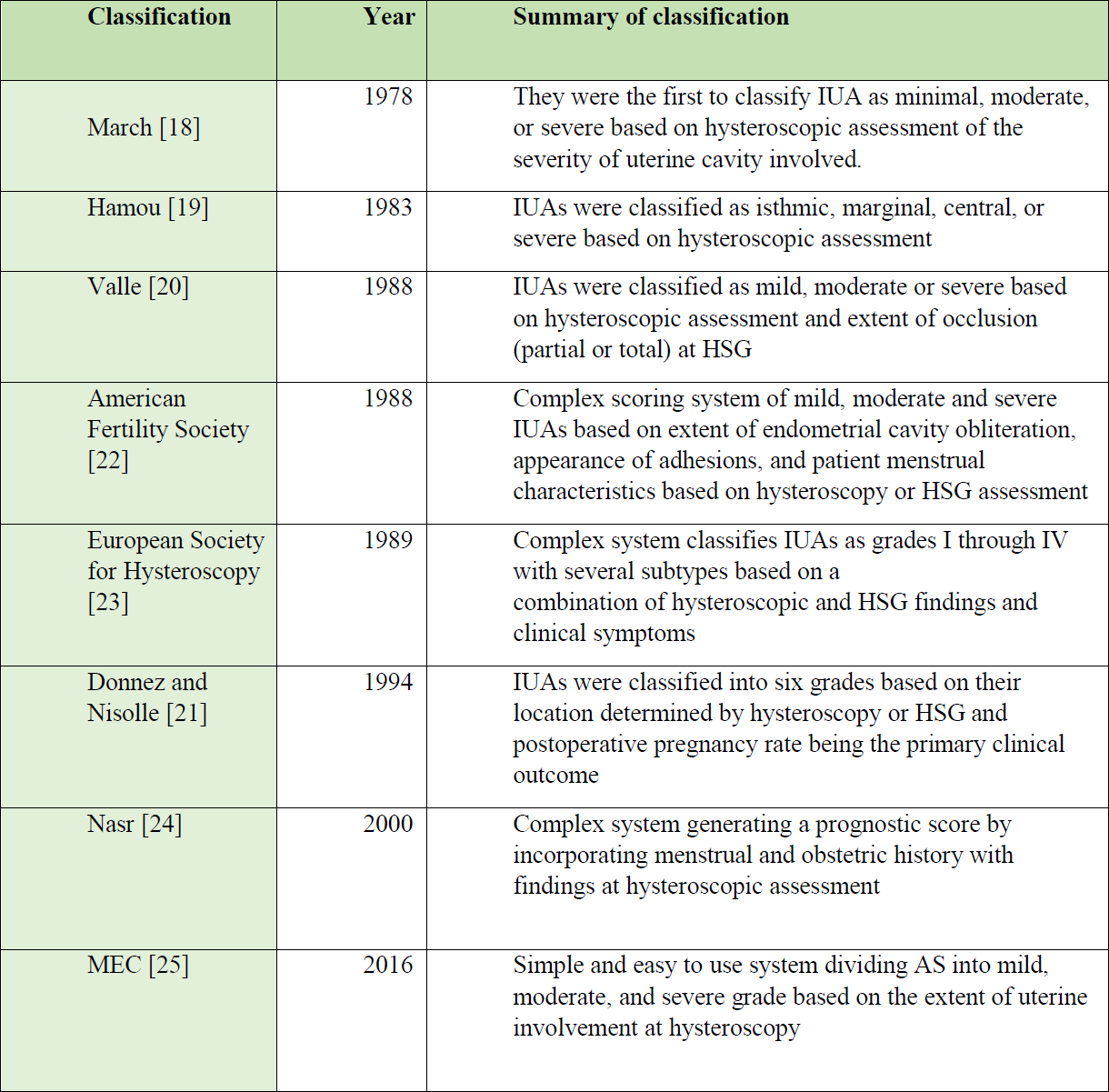

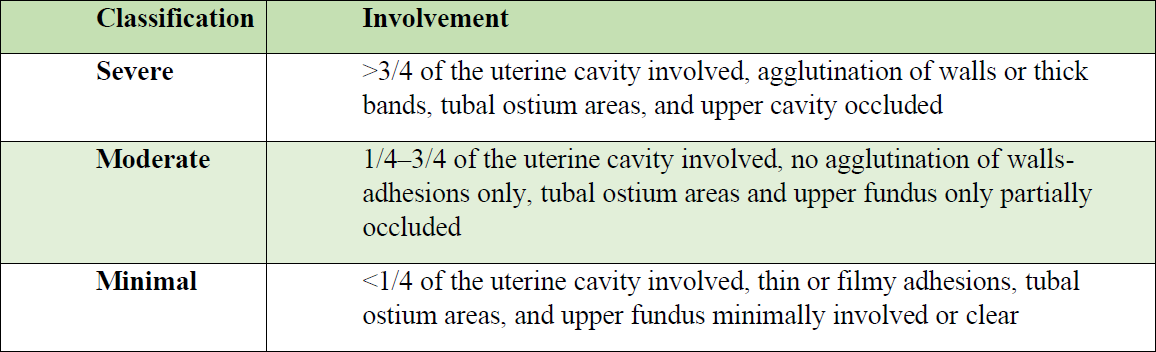

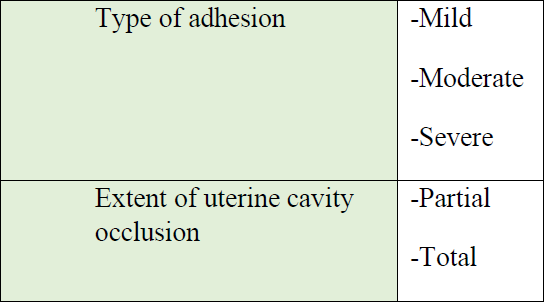

There is a need to classify IUAs (as depicted in Table 1) so that it can serve as a guide to the prognosis after a treatment, which in itself is linked to the disease severity [17]. March classification. March et al. in 1978 were the first ones to categorize IUAs based on hysteroscopic findings into minimal, moderate, and severe. The criteria used to grade the severity of IUAs was extent of adhesions present in the endometrial cavity and the degree of its occlusion. This classification system is still used because it is simple to use and easy to remember (Table 2.1). However, the shortcoming of this classification system is that there is no correlation with clinical symptoms and the post-treatment success was not defined [18].

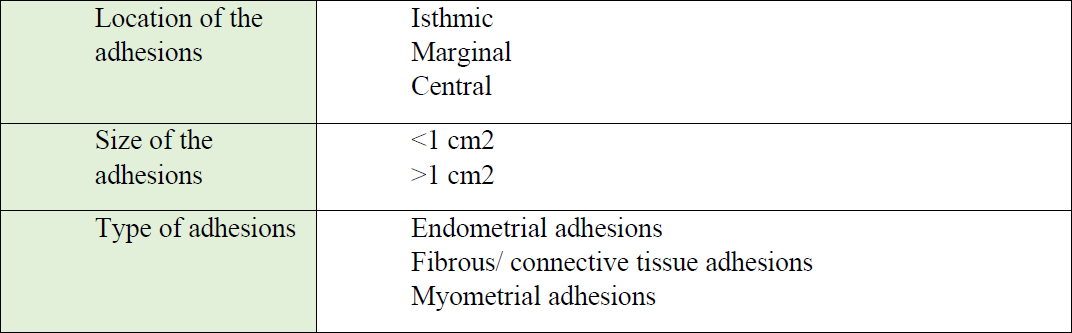

In 1983, Hamou et al. also included the extent and histologic nature of the adhesions as well as the evaluation of the surrounding glandular endometrium along with the degree of cavity distortion. (Table 2.2) [19].

The three types of adhesions described in his study are as follows:

- Endometrial adhesions: white, vascularization similar to the surrounding endometrium

- Fibrous or connective tissue adhesions:transparent, bridge-like and poorlyvascularized

- Myometrial adhesions: highly vascularand extensive adhesions

The different types of adhesions identified were as follows:

- Mild: filmy adhesions composed ofendometrial tissue causing partial orcomplete endometrial cavity occlusion.

- Moderate: fibromuscular adhesions,made up of endometrium causingpartial or total occlusion of theendometrial cavity, can bleed onadhesiolysis.

- Severe: dense connective tissueadhesions, lack endometrial tissue andcausing partial or total occlusion of theendometrial cavity, not likely to bleedon adhesiolysis.

In an attempt to reduce the shortcomings of the previous classification systems, in 1988, Valle et al. suggested that success of treatment, identified by improvement in menstrual pattern, and reproductive outcomes, also had to be correlated with the severity of disease. This classification system thus included both the extent of endometrial cavity involvement as well as the type of adhesions [20] (Table 2.3).

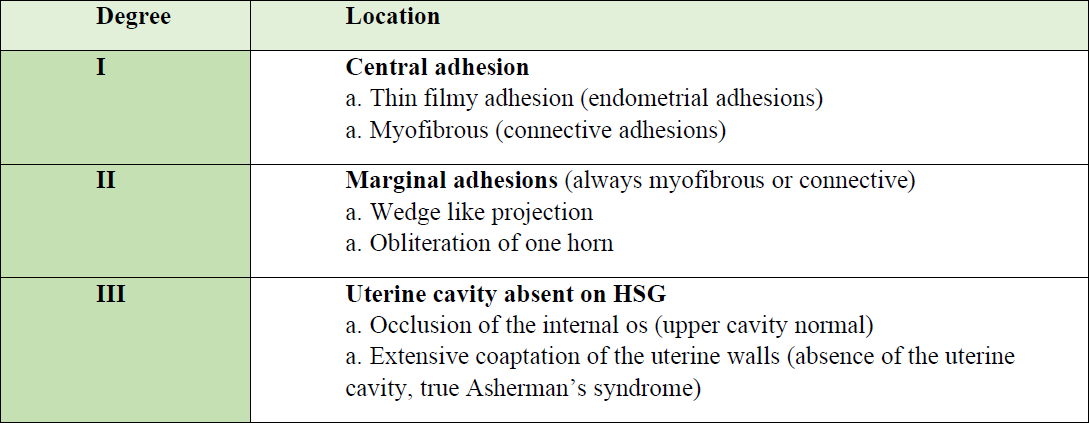

Donnez and Nisolle classification. In 1994, Donnez and Nisolle re-emphasized the importance of using HSG in the classification of AS along with hysteroscopic finding and proposed a classification system based on both modalities. They broadly divided AS into three groups and six subgroups depending on the type of adhesion and the extent of uterine involvement as described in Table 2.4 [21].

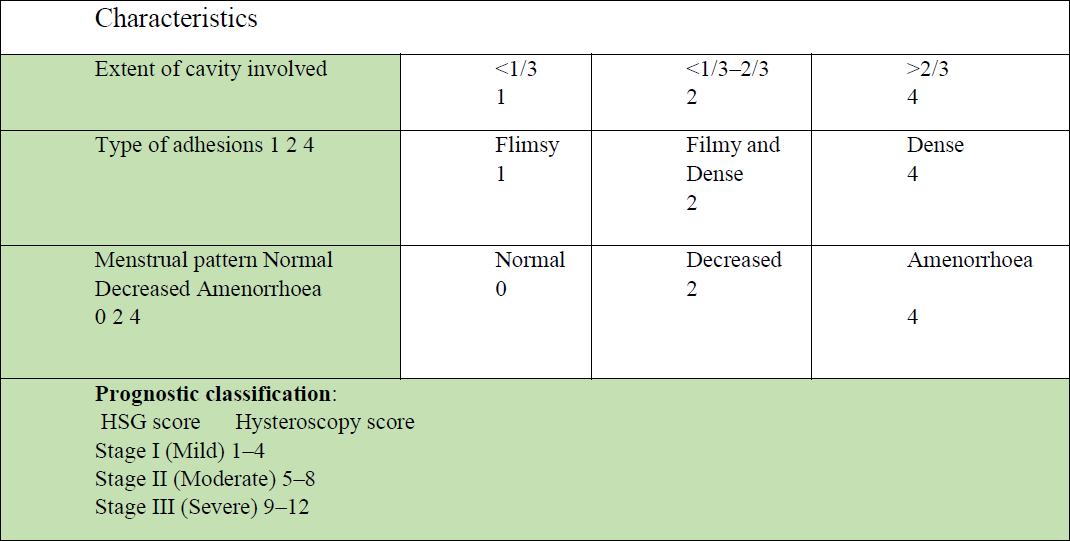

The American Fertility Society (AFS) introduced a comprehensive classification system that became the most widely accepted IUAs classification system across the globe. It included the clinical symptoms (menstrual pattern) as an indicator of disease severity, which was considered important as it gives an estimate about the amount of endometrium which was available for potential regeneration post-adhesiolysis and serves as an important marker for defining the prognosis post-treatment, thus helping in pre-treatment patient counselling. Scoring points (1–3) were given to each of the included characteristics and staging of AS was done (stage I/II/III: mild/moderate/severe) according to the score obtained. Additionally, a prognostic score to each patient was for the first time assigned by a classification system and hence it became a more objective way of classification (Table 2.5) [22].

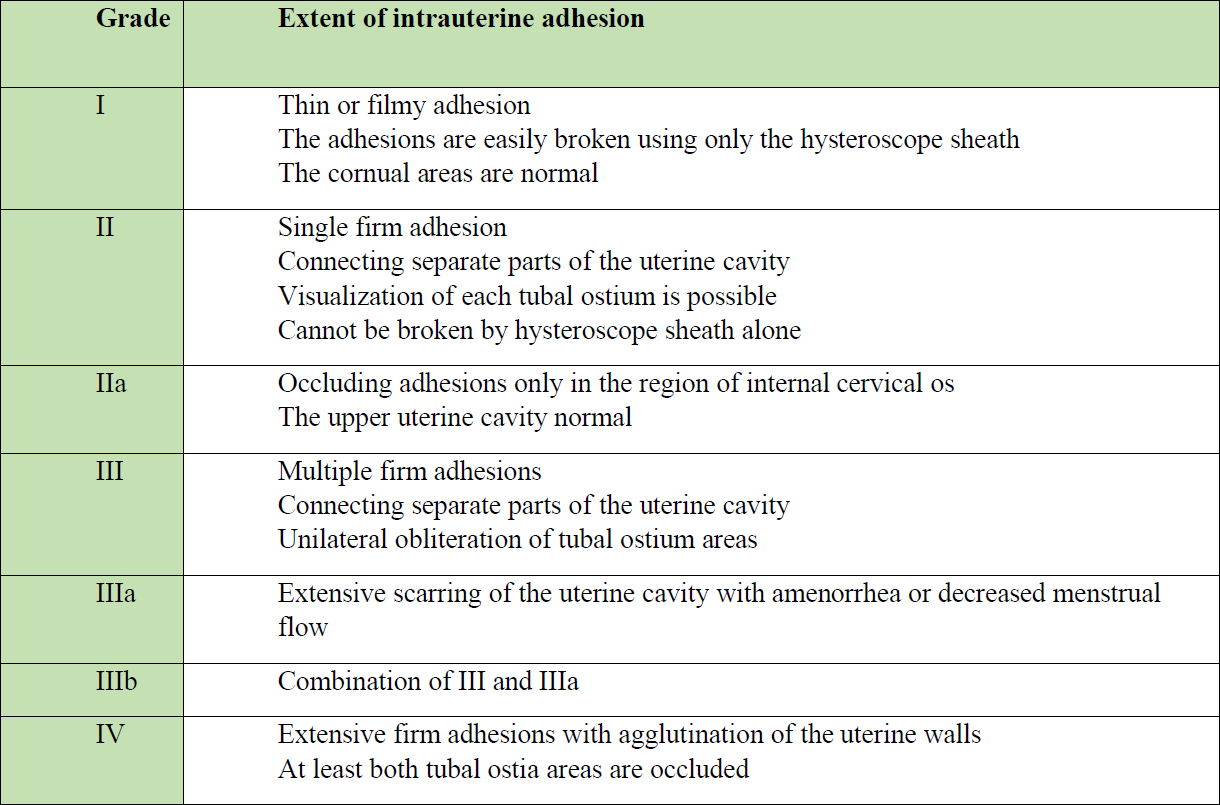

Another classification system was proposed by the European Society of Hysteroscopy (ESH) in 1989, incorporating the menstrual pattern of women with IUA (as per table 2.6). However, the reproductive outcome of patients, which is one of the important aspects in cases of IUA, was not included. Another disadvantage of this classification system was that, despite it being a very comprehensive system for grading, its complexity makes it difficult to remember and use in clinical practice, thus limiting its utility [23].

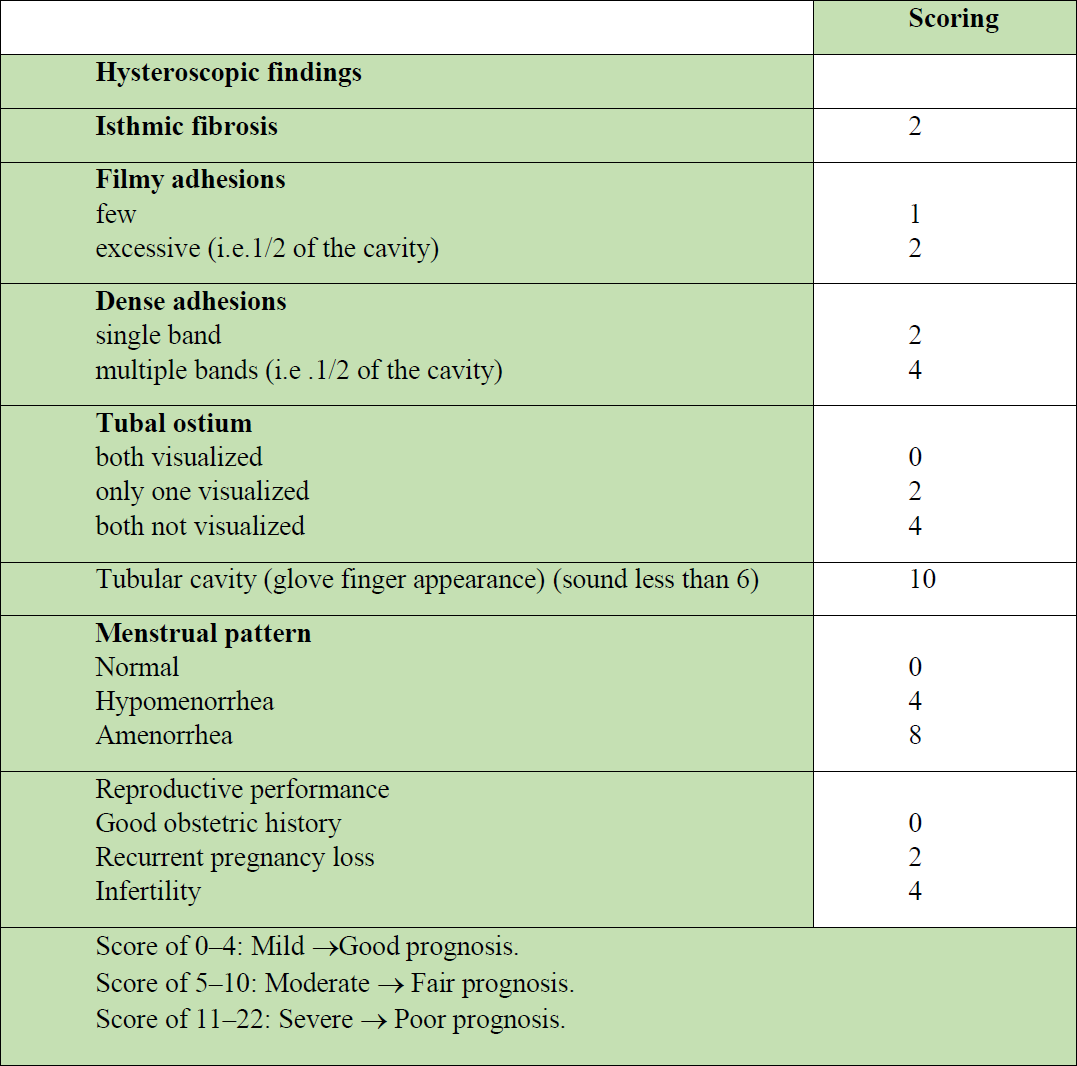

Nasr classification. Nasr et al. (2000) described a very comprehensive scoring system including the clinical symptoms (both menstrual pattern and reproductive outcomes) of the patients and the hysteroscopic findings along with providing a prognostic correlation as described in Table 2.7.

This system gives greater emphasis on the type of adhesions and the ability to visualize the tubal ostium over the involvement of the rest of the endometrial cavity.

Adhesions were pathologically classified into three categories: filmy/dense/tubular. The latter, which is the most severe form of the disease, indicates dense adhesions obliterating the entire uterine cavity, thereby obscuring both the tubal ostia. Isthmic fibrosis was identified as a separate entity and was given special importance as it could initiate a neuroendocrine reflex and cause endometrial deactivation and amenorrhea even when the rest of the cavity is free of adhesions [24].

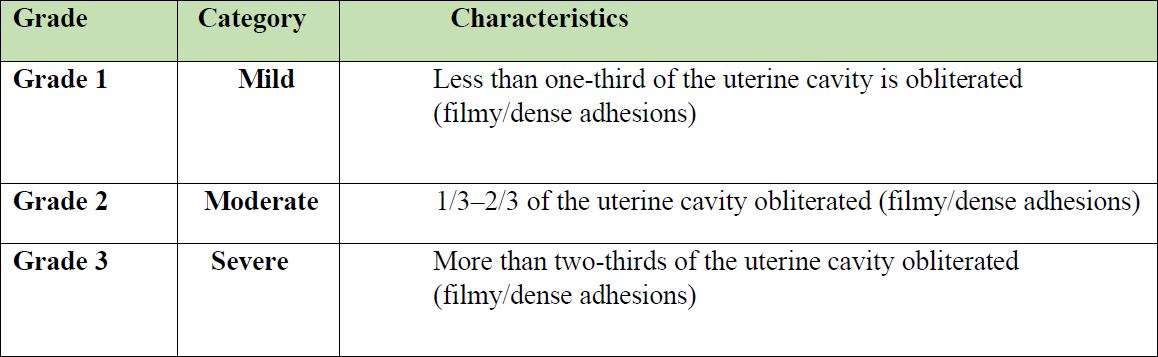

MEC classification. In 2016, the Manchanda’s Endoscopic Centre (MEC) classification system was proposed in India, which categorized IUAs as mild, moderate, and severe disease owing to the extent of the endometrial cavity involvement. It encompasses both dense and flimsy adhesions in all categories. Its advantage is of being relatively simple and easy to use in clinical practice [25] (Table 2.8).

The reproductive outcomes based on this classification system were correlated with the severity of the adhesions in a retrospective analysis performed in 2018 by Sharma et al., who reported an increased number of live births after adhesiolysis in the moderate and severe categories of adhesions. The direction and degree of adhesiolysis performed by hysteroscopy were guided by preoperative assessment of myometrial thickness of fundal, anterior, and posterior uterine walls using the ‘RR’ method in this study [26].

The ‘RR method’ is named after the two main authors of this paper and refers to the measurement of myometrial thicknesses both at the fundus of the uterus and at anterior/posterior uterine walls, that guides the amount and the direction of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis [26].

Conclusion

It is necessary to evaluate the extent of intra-uterine adhesions, in order to select the best treatment option in managing menstrual and infertility problems and analysing the postoperative success of adhesiolysis, hence hysteroscopic classification systems are useful. By and large AFS classification is the most widely accepted among these scoring systems which is a clinic-hysteroscopic classification. MEC classification is the most recent classification system, which is hysteroscopy-based scoring system that has been developed in 2016 in India and is relatively simple and easy to implement under clinical settings. A universally agreed upon classification system is needed to predict post-treatment reproductive outcomes according to the severity of the condition. MRI is not a cost-effective diagnostic tool for the IUAs. Hysteroscopy is cost-effective tool to get a real time view of the uterine cavity which helps in accurate description of intrauterine adhesions and assesses its severity and treatment can also be provided in the same setting hence it is time saving procedure as well.

References

Figure 1. Diagnostic scheme for IUAs

Figure 2. Steps to identify IUA on office hysteroscopy

Figure 3. From left to right: normal cavity; mucosal adhesions; fibromuscular adhesions

Figure 4. Isthmic adhesions. F: fibrous; M: mucosal

Figure 5. Thick adhesions. FM: fibro-muscular; IUA: Intrauterine adhesions; AA: After adhesiolysis

Table 1. Various hysteroscopy-based classification systems for IUAs

Table 2.1. Detailed classification of Intra uterine adhesions by March, 1978

Table 2.2. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by Hamou, 1983

Table 2.3. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by Valle, 1988.

Table 2.4. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by Donnez and Nisolle, 1994

Table 2.5. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by American Fertility Society (AFS), 1988

Table 2.6. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by European Society of Hysteroscopy (ESH) 1989

Table 2.7. Classification of Intra uterine adhesions by Nasr, 2000

Table 2.8. MEC classification of Intra uterine adhesions